Developing a New Research Method, Part 2: Introduction to Archivevoice

By Prakash Krishnan, 2024 Research FellowMany of my previous projects centre observational analysis of photography in community group settings. As my practice developed, I was led to the participatory research method called Photovoice. In 2016, Apaza & DeSantis documented a five-phase process methodology for the Photovoice method, and I am applying and extending it to selection and processing of archival photography and documentation that respond to researchers’ questions. I am calling this extension “Archivevoice.” But before I go deeper into that, let’s outline our framing, starting with the basics.

What is an archive?

At its simplest, an archive is a repository of historical records like photographs, documents, sound recordings, books and artworks. Speciality archives may focus on a particular medium, such as the Moving Image Archive or a place, like the London Metropolitan Archives. Archives house physical or digital records or a combination of both. Many archives are found within larger institutions such as universities, libraries, museums, government offices, and established public or private organizations. Usually, these archives have their materials grouped into collections managed by professionals called archivists.

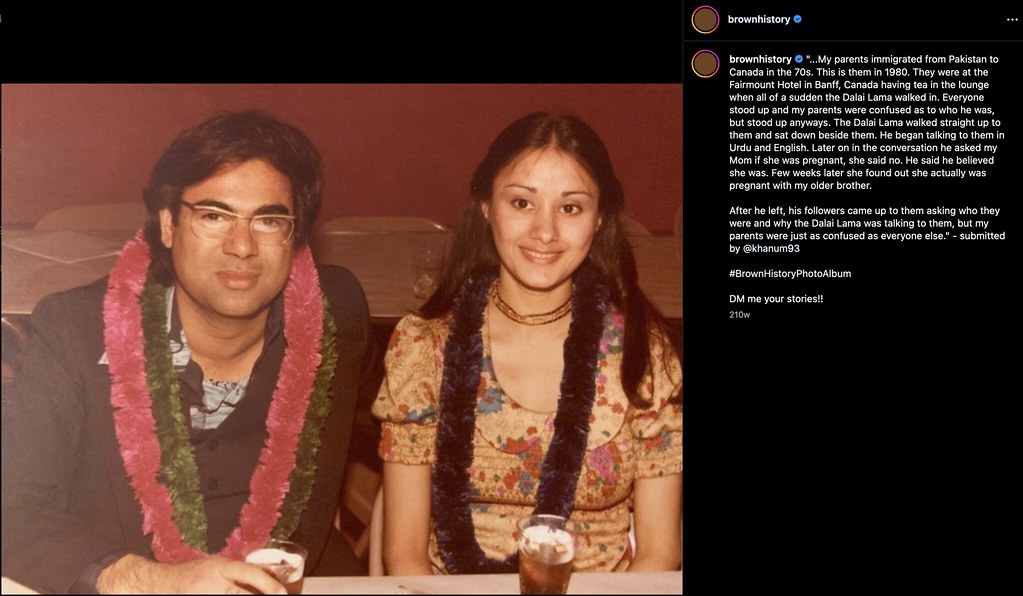

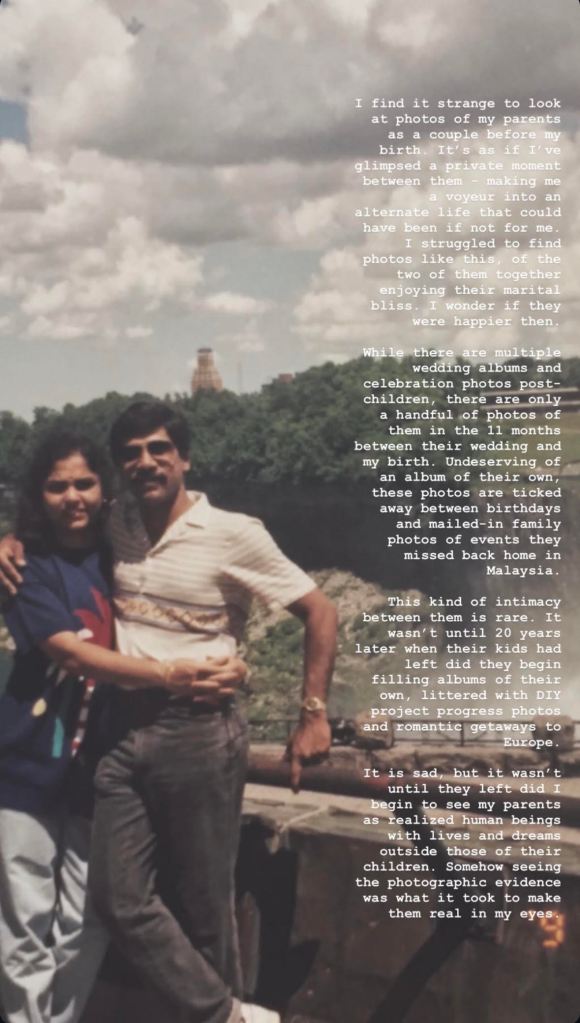

There are all kinds of informal archives as well. Lots of smaller community and cultural organizations keep records of their activities but may not have a dedicated archivist to keep them organized. We, individuals, also record our lives through photography, sometimes printing them or keeping them in digital photo albums, or online on various social media platforms like Instagram, Facebook, or Flickr.

What is Photovoice?

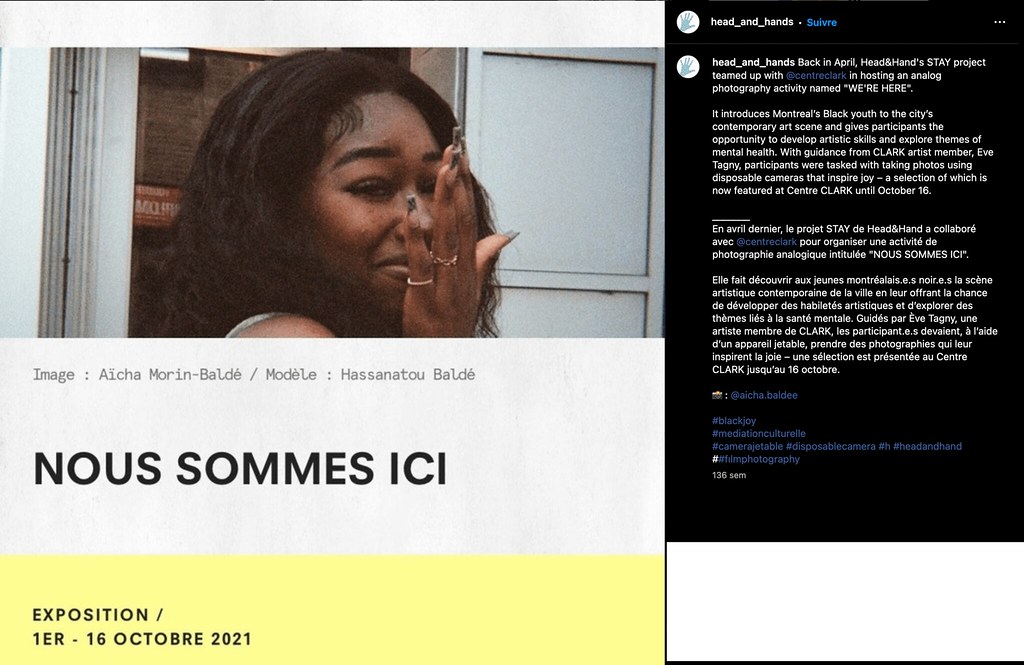

Originally conceived and put into practice by health researchers Caroline Wang and Mary Ann Burris in the early 1990s, Photovoice involves working alongside participants to take photographs and subsequently discuss them in order to be able to collectively illuminate and reflect upon contemporary issues within a community. At the end of the project, a selection of the photos taken and discussed is exhibited for the community to share the insights that were collectively produced. Often, researchers engaging in Photovoice seek to recalibrate the power imbalance between researcher and subject by lending the tools for research (i.e. the camera) to the active participants, thus elevating them to the position of collaborator, co-researcher, or co-producer.

Archivevoice is an extension of Photovoice, alongside others like Videovoice and Comicvoice. By using the principles of participatory action research developed in Photovoice, other researchers have modified their methods engaging in different artistic mediums for participants’ self-expression. Videovoice has the goal of getting “people, who are usually the subjects or consumers of mainstream media [to] get behind video cameras to research issues of concern, communicate their knowledge, and advocate for change.” Comicvoice, coined by John Baird, engages research groups in creating their own narratives from outsourced comics.

Why Archives?

There is so much rich, historical information available within archives. One of the limits of the Photovoice method is what is available to be photographed. Through Archivevoice, the research participants are able to navigate through much broader windows of time and space to reflect and discuss how historical events shape the contemporary moment. This kind of embodied practice of looking back and critically engaging with one’s community and culture through such a deep, reflective practice has been referred to by scholars as “ancestor work”.

Archivevoice

Archivevoice is a Participatory Action Research (PAR) method that adapts the core principles of Photovoice using photographs or other archival documentation to undergo community-centered research.

“Through exhibitions and outreach events community members can be brought to the archive and made aware of what records are present in the archives. They can see themselves, their families, and their histories represented in the materials and engage with those who are responsible for preserving and describing that history. Through workshops and naming events, the archives can be brought to community members for the purpose of facilitating discussion, memory making, and healing together.”

– Kristen Young

What is the purpose of Archivevoice?

- To use photographs and other archival documentation to reflect on collective experiences affecting communities

- To gain insight about a particular community’s histories, activities, and concerns

- To engage communities with their own archival records

- To empower communities to lend their voice to heritage projects and document their own histories

- To have community participants be co-producers of research

- To activate the archive through creative presentation of the selected records (e.g. exhibition, zine, phonebook, etc.)

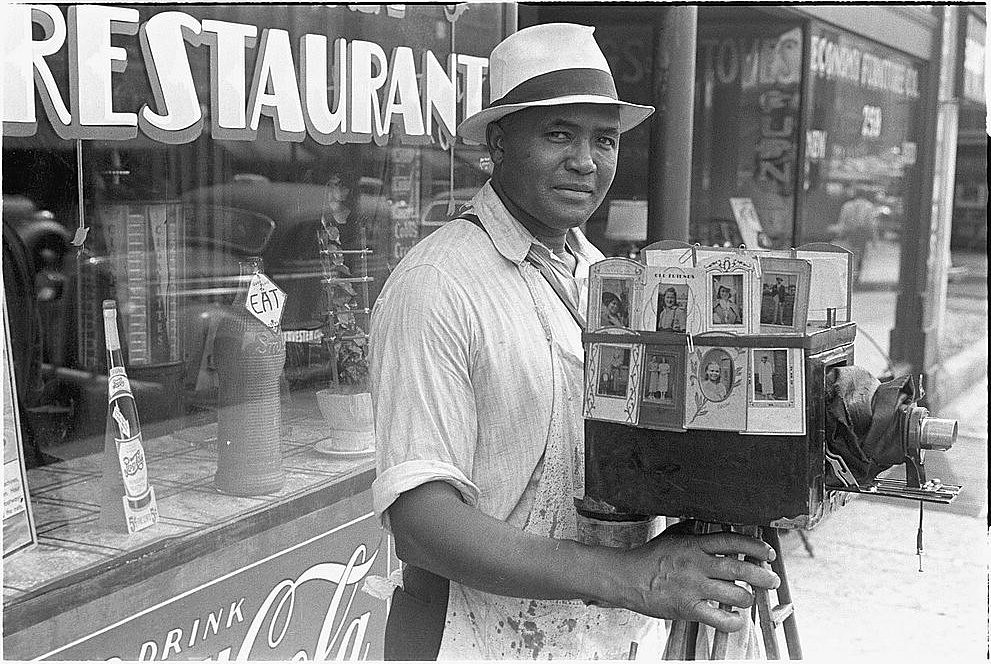

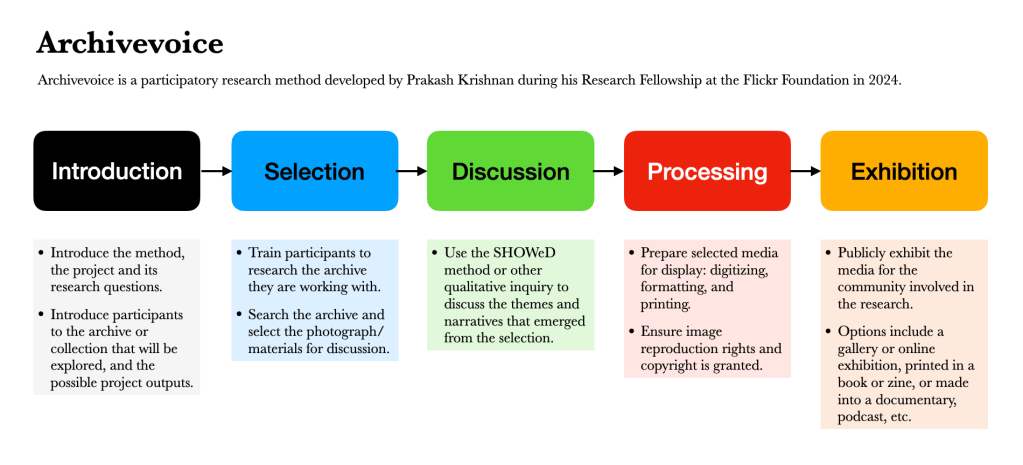

Full size image

How could I run an Archivevoice session?

Archivevoice borrows the same five-phase approach outlined in Vanese Apaza and Phoebe DeSantis’s 2016 Facilitator’s Toolkit for a Photovoice Project, with the authors’ permission. The five phases adapted to Archivevoice are as follows:

Phase 1: Introduction to Archivevoice

Introducing the method, the project and its research questions. Introduce participants to the archive or collection that will be explored, and the possible project outputs.

Phase 2: Selection of archival photos or other documentation

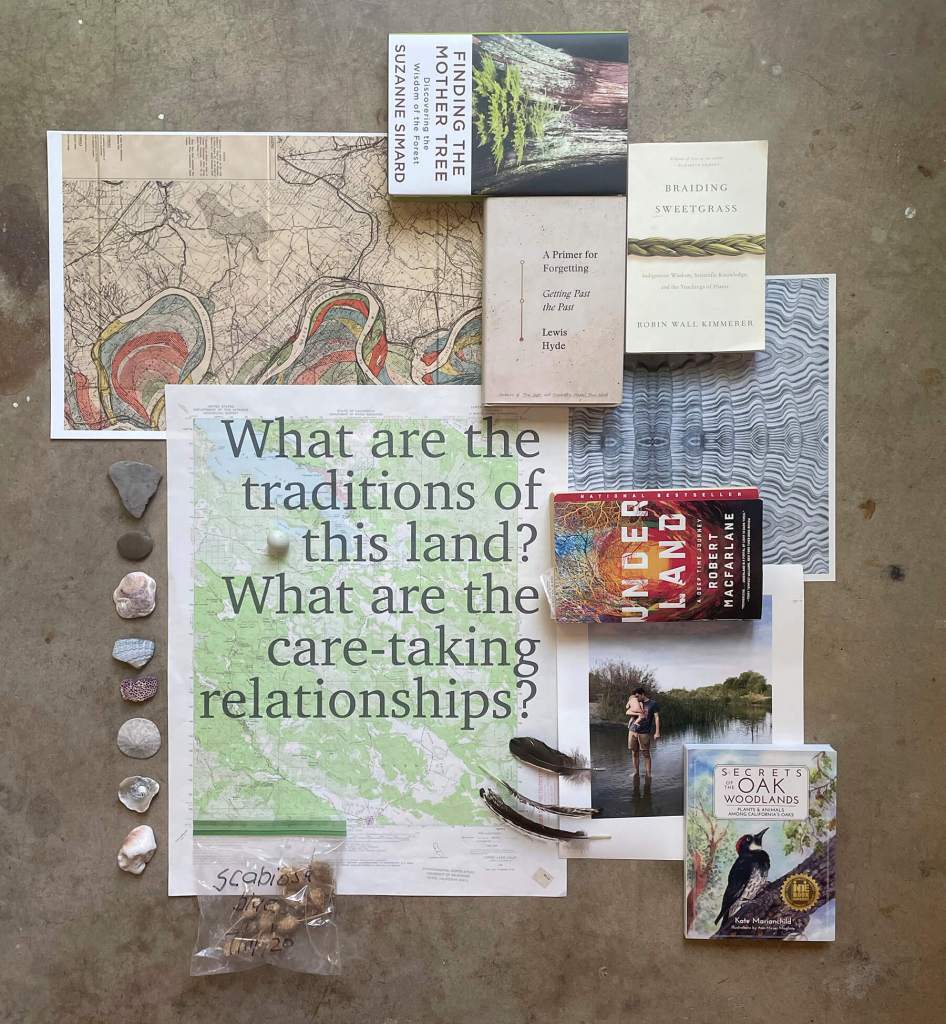

In Archivevoice, this phase replaces the photo-taking step in Photovoice. This is when the participants will receive archive research training tailored to the particular archive they are working with. They search the archive and select the photographs or other materials they wish to discuss. The project manager or lead researcher may want to preselect the items available for study (e.g. limiting the search within specific collections or setting specific inclusion criteria such as using materials with ‘no known copyright restrictions’).

Phase 3: Discussion around selected media

Just as in Apaza & DeSantis’ process, the “SHOWeD” method can be used to prompt the research participants to discuss the selected media.

SHOWeD is an acronym used in community-based health care research inspired by the pedagogical teachings of Paulo Freire.

S – What things did you see?

H – What was happening?

O – Does this happen in our community?

W – Why does this happen?

D – What can we do about it?

While SHOWeD has a long history of being used in conjunction with Photovoice, other reflection and discussion methods such as focus groups, semi-structured interviews, and narrative writing are also possible or can be used in conjunction with SHOWeD depending on what is deemed appropriate or relevant by the lead researcher.

Phase 4: Media processing for archive activation

Here the selected archival media must be prepared for display. This could involve ensuring that the researcher has the appropriate rights or permissions to reproduce the identified media, that copyright is granted (or no known copyright restrictions are applied), and digitizing, formatting, and printing.

Phase 5: Community exhibition or other public output

Photovoice projects often culminate in a public exhibition for the community who were the subjects of the photos taken during the project. Similarly, once proper permissions are secured for the selected archival media, an exhibition of these items can be produced either physically – in the archive itself or gallery or community centre or online. Other options for public presentations of these selected media could be a book or zine, online exhibition, documentary, podcast, and more.

Archivevoice serves as an adaptation of Photovoice to facilitate engagement with archival intervention and activation. According to Freire, “education must begin with the solution of the teacher-student contradiction, by reconciling the poles of the contradiction so that both are simultaneously teachers and students.” In this sense, a critical pedagogy requires both parties, “teachers” and “students” to understand that they each have something to learn from the other and that knowledge can be freely transferred from one to another. Participants who become de facto co-researchers in these projects in which they are given relative autonomy to express themselves through the selected media (e.g. photo, video, comic, archive, etc.) are empowered to have their feedback and knowledge heard and understood and they make planning and curatorial decisions. By elevating their status to co-researchers and collaborators,

Archivevoice and the other -voice projects dissolve knowledge hierarchies asserting that lived experience and community knowledge merit their place in research and public pedagogy projects.

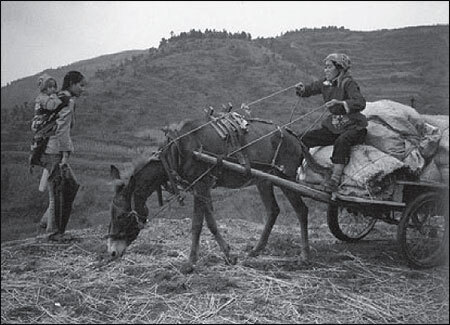

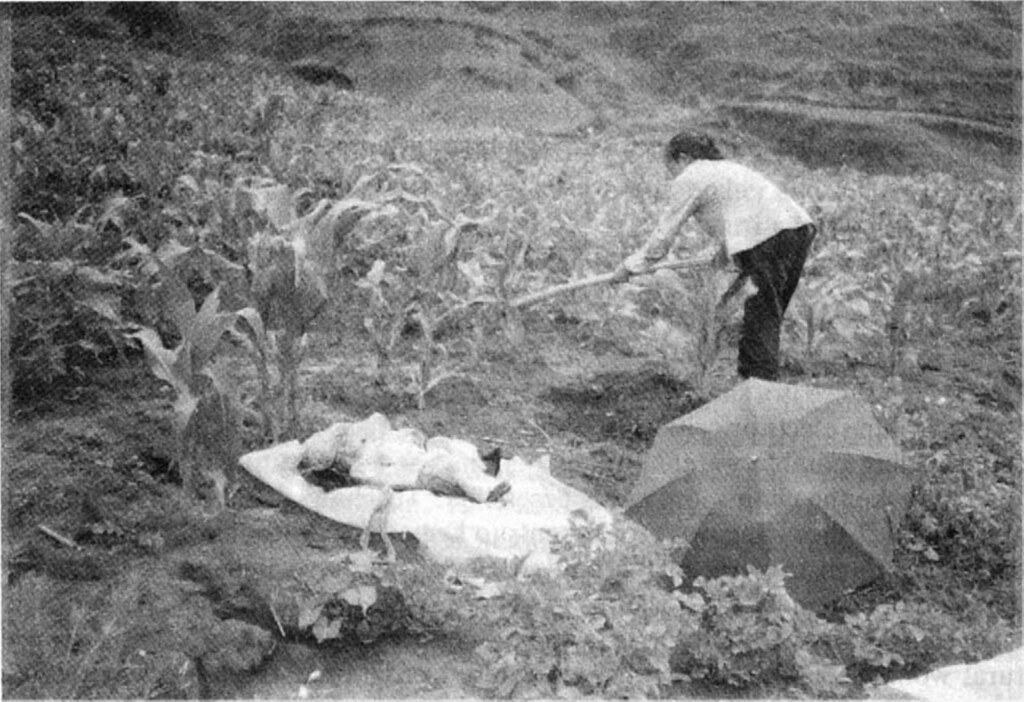

For my final blog post—coming soon—I will report on my own investigation of the Archivevoice method, through a workshop I ran recently in Montreal with researchers from the Access in the Making Lab located at Concordia University in Montreal, Canada. Members from the lab are currently engaged in a project researching the disabling conditions that climate change and systems of extraction are having on various populations and ecosystems around the world. Together, we went through the steps of the Archivevoice method using Flickr as its source archive, looking for and discussing images that related to the researchers’ individual projects. The vast quantity of photos available in the Flickr archive prompted many interesting topics of discussion that will be explored in part three of this series.

Bibliography

Apaza, Vanesa, Phoebe Desantis, Aurea DeLeon, Jaclyn Keelin, Alexandra Ovits, Sherrine Schuldt, and Michael Spillane. “Facilitator’s Toolkit for a Photovoice Project.” United for Prevention in Passaic County and the William Paterson University Department of Public Health, 2016. https://www.up-in-pc.org/clientuploads/Whatwedo/Flyers/UPinPC_Photovoice_Facilitator_Toolkit_Final.pdf.

BAIRD, John Loige. “Comicvoice: Community Education through Sequential Art.” In POP CULTURE ASSOCIATION ANNUAL MEETING, Vol. 13, 2010.

Catalani, Caricia E. C. V., Anthony Veneziale, Larry Campbell, Shawna Herbst, Brittany Butler, Benjamin Springgate, and Meredith Minkler. “Videovoice: Community Assessment in Post-Katrina New Orleans.” Health Promotion Practice 13, no. 1 (January 1, 2012): 18–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839910369070.

Freire, Paulo, Donaldo P. Macedo, Ira Shor, and Myra Bergman Ramos. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. 50th anniversary edition. 1 online resource (viii, 220 pages) vols. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018. https://nls.ldls.org.uk/welcome.html?ark:/81055/vdc_100055048362.0x000001.

Shaffer, Roy. “Beyond the Dispensary.” English Press: Nairobi, Kenya, 1986. https://www.amoshealth.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/62/2019/10/Beyond-the-Dispensary.pdf.

Young, Kristen. “Black Community Archives in Practice.” In Black Community Archives in Practice, 211–21. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780228019152-011.