Making A Generated Family of Man: Revelations about Image Generators

Juwon Jung | Posted 29 September 2023I’m Juwon, here at the Flickr Foundation for the summer this year. I’m doing a BA in Design at Goldsmiths. There’s more background on this work in the first blog post on this project that talks about the experimental stages of using AI image and caption generators.

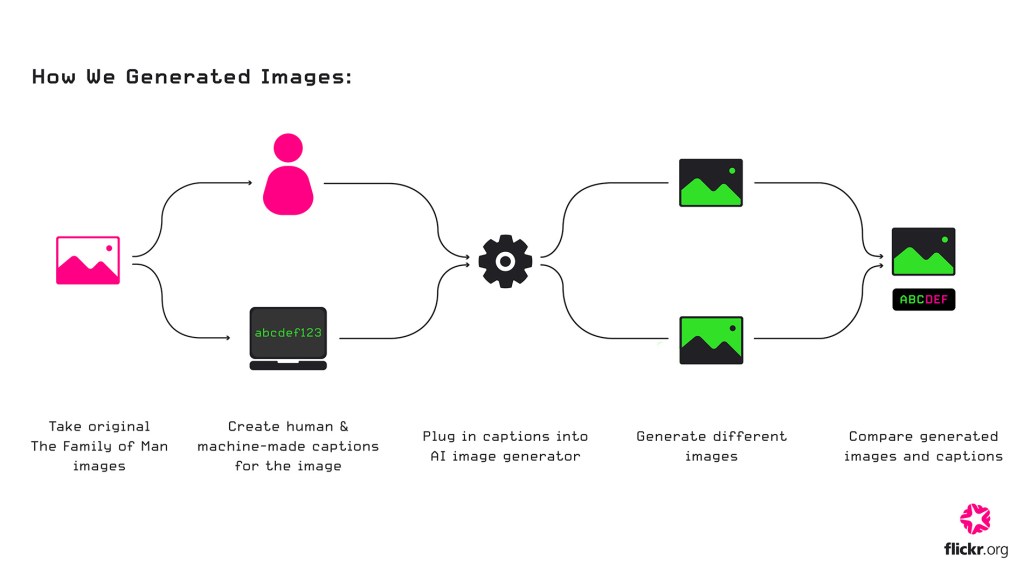

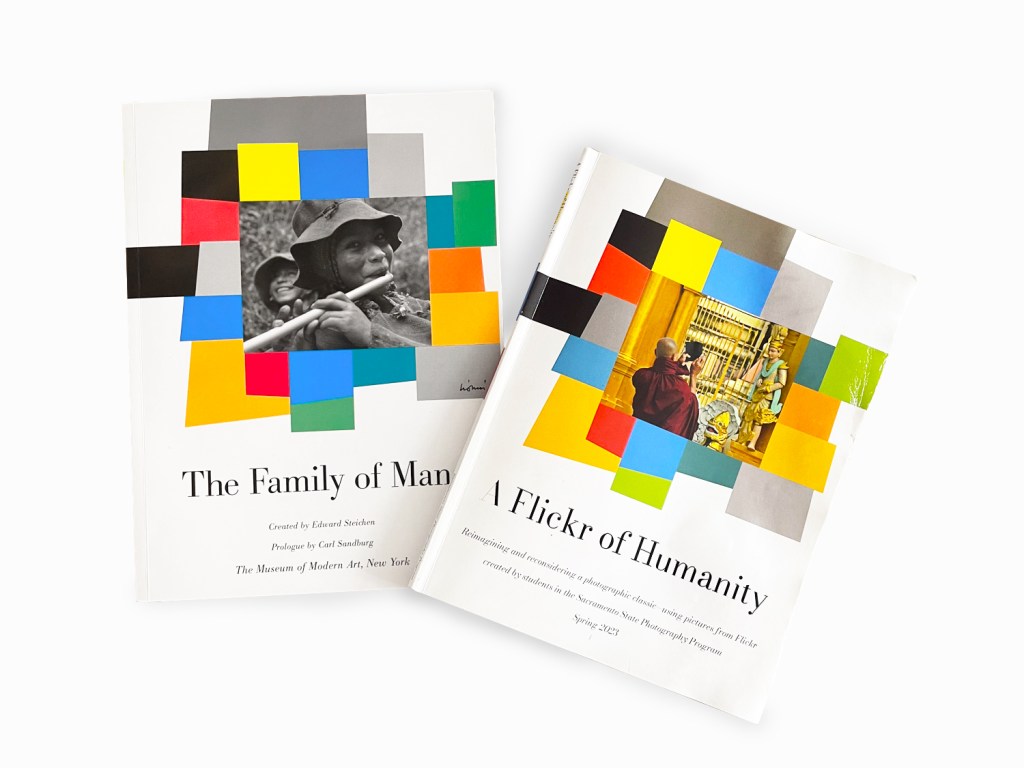

“What would happen if we used AI image generators to recreate The Family of Man?”

When George first posed this question in our office back in June, we couldn’t really predict what we would encounter. Now that we’ve wrapped up this uncanny yet fascinating summer project, it’s time to make sense out of what we’ve discovered, learned, and struggled with as we tried to recreate this classic exhibition catalogue.

Bing Image Creator generates better imitations when humans write the directions

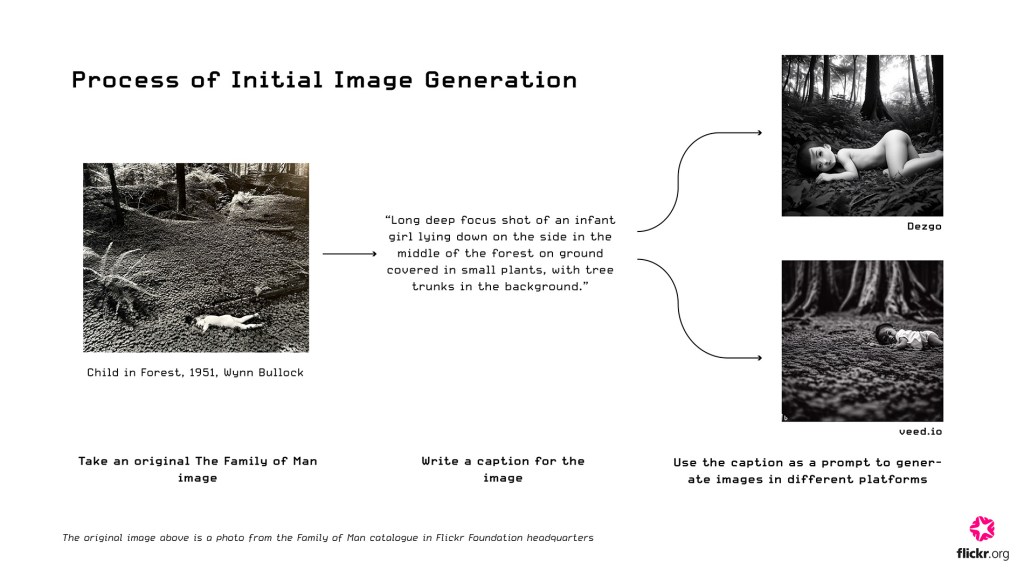

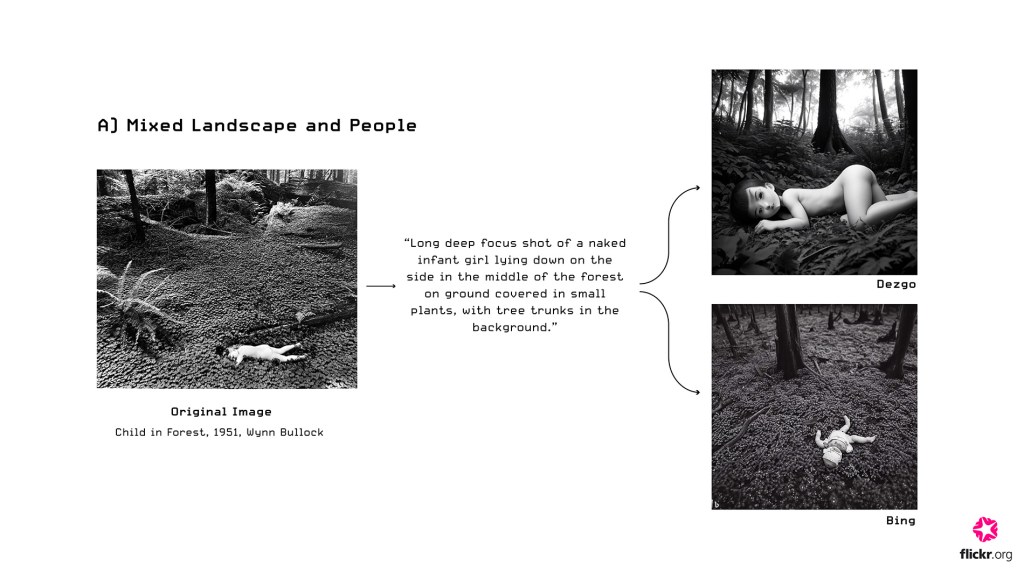

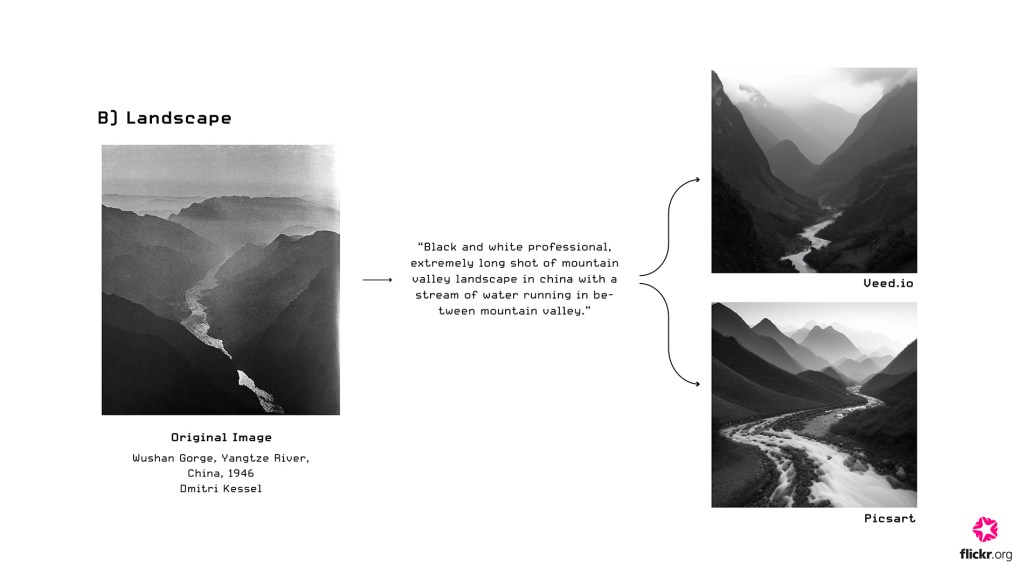

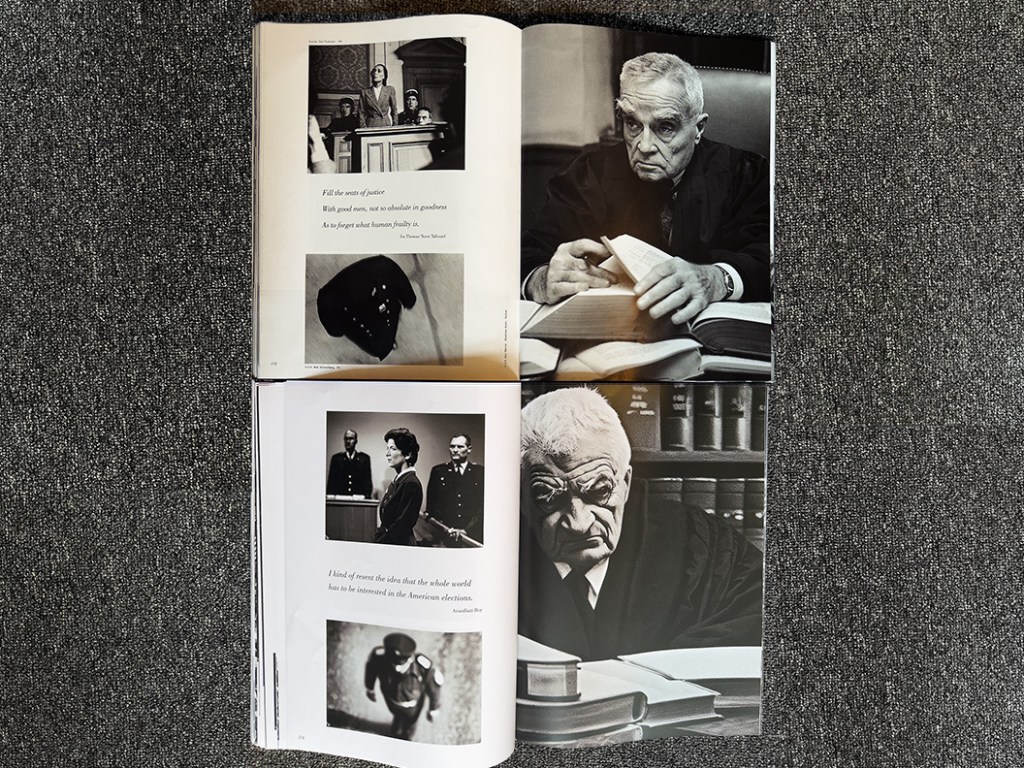

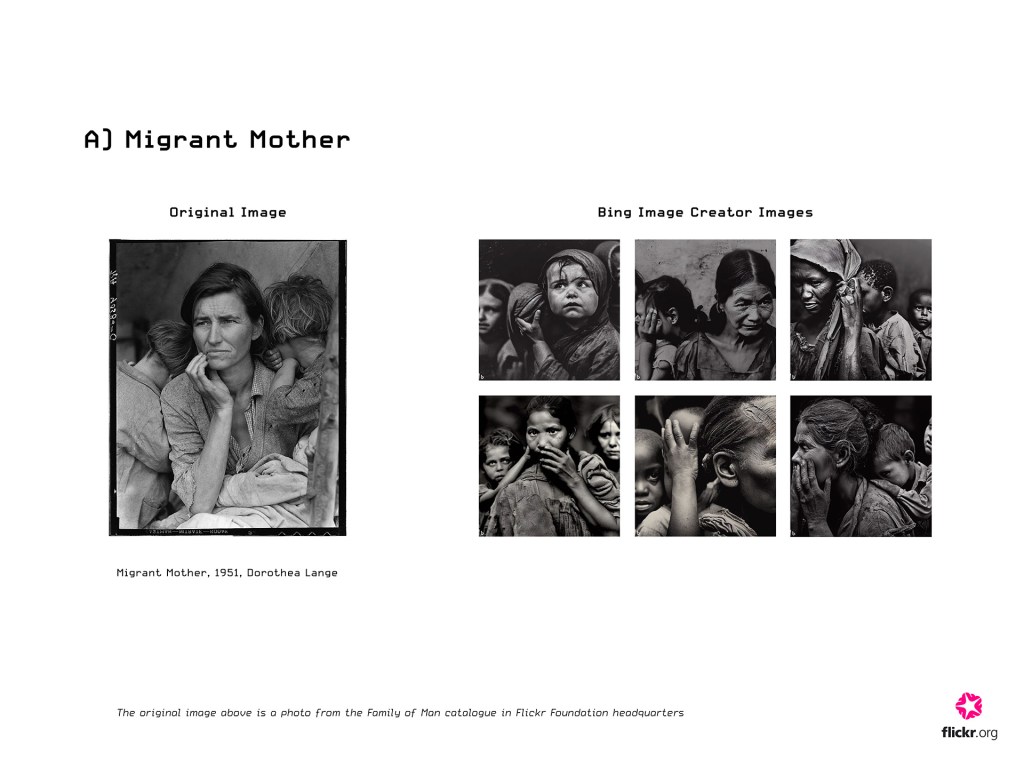

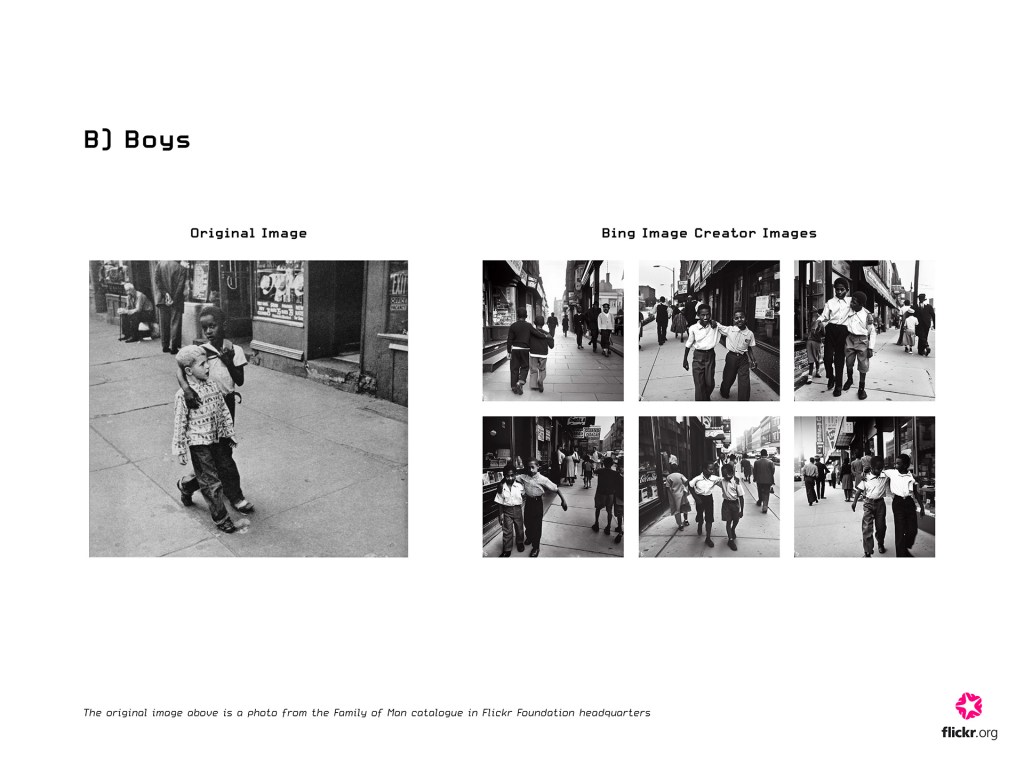

We used the Bing Image Creator throughout the project and now feel quite familiar with its strengths and weaknesses. There were a few instances where the Bing Image Creator would produce surprisingly similar photographs to the originals when we wrote captions, as can be seen below:

Here are the caption iterations we made for the image of the judge (shown above, on the right page of the book):

1st iteration:

A grainy black and white portrait shot taken in the 1950s of an old judge. He has light grey hair and bushy eyebrows and is wearing black judges robes and is looking diagonally past the camera with a glum expression. He is sat at a desk with several thick books that are open. He is holding a page open with one hand. In his other hand is a pen.

2nd iteration:

A grainy black and white portrait shot taken in the 1950s of an old judge. His body is facing towards the camera and he has light grey hair that is short and he is clean shaven. He is wearing black judges robes and is looking diagonally past the camera with a glum expression. He is sat at a desk with several thick books that are open.

3rd iteration:

A grainy black and white close up portrait taken in the 1950s of an old judge. His body is facing towards the camera and he has light grey hair that is short and he is clean shaven. He is wearing black judges robes and is looking diagonally past the camera with a glum expression. He is sat at a desk with several thick books that are open.

Bing Image Creator is able to demonstrate such surprising capabilities only when the human user accurately directs it with sharp prompts. Since Bing Image Creator uses natural language processing to generate images, the ‘prompt’ is an essential component to image generation.

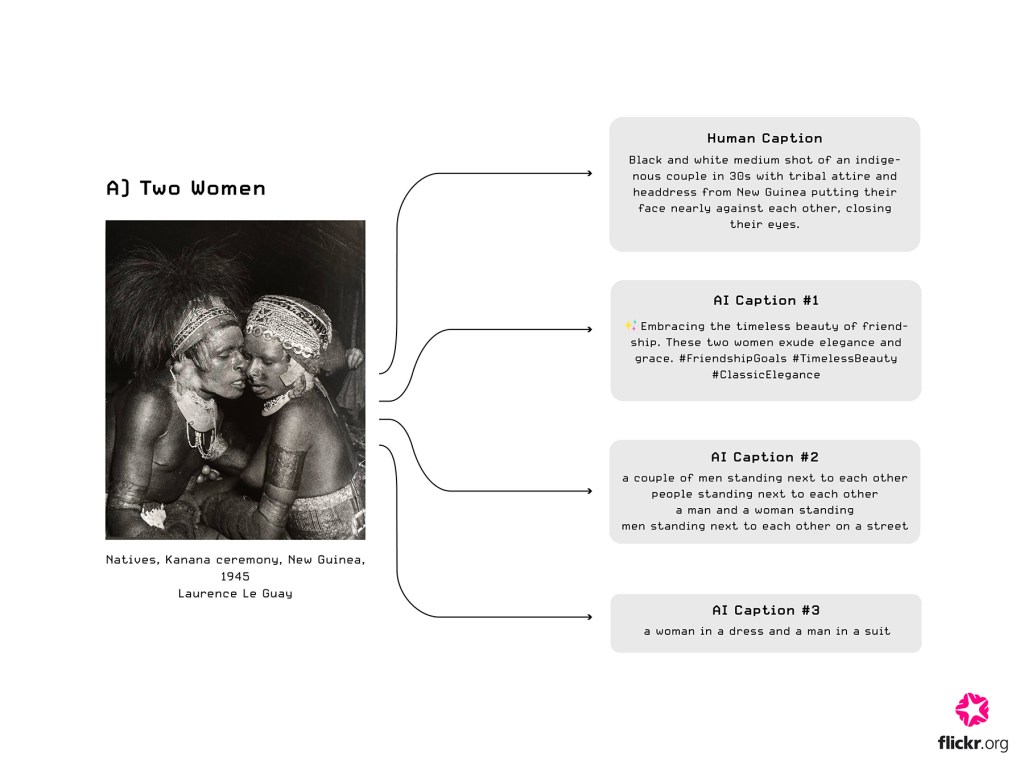

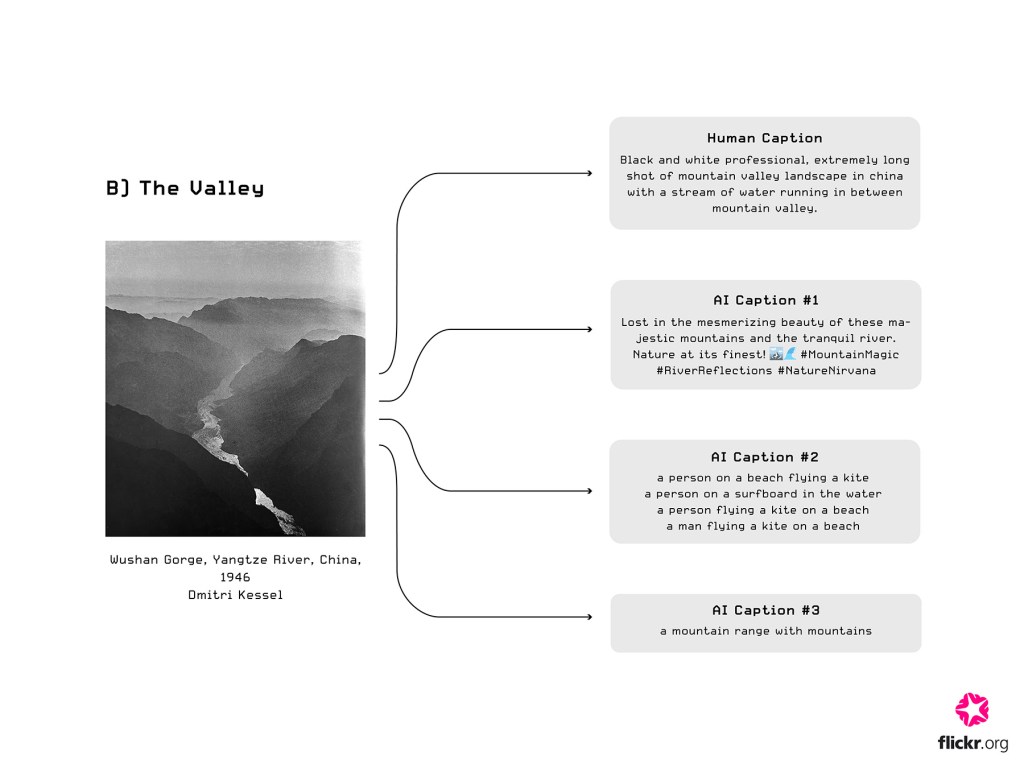

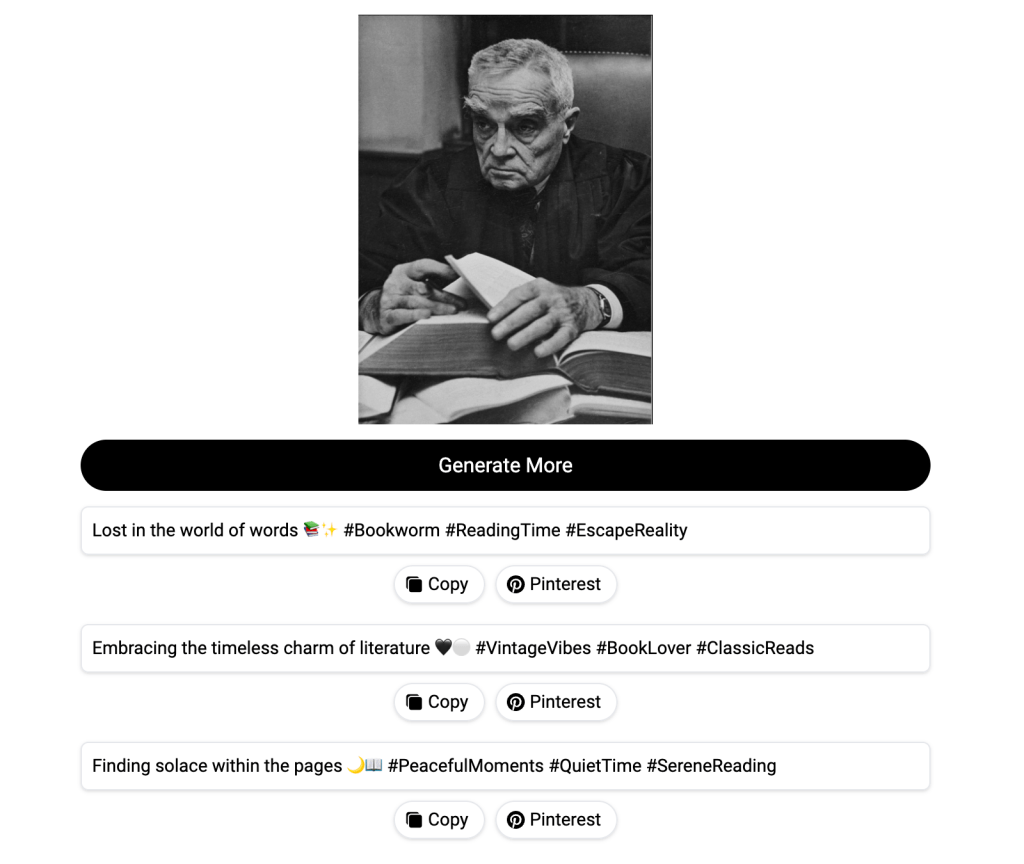

Human description vs AI-generated interpretation

We can compare human-written captions to the AI-generated captions made by another tool we used, Image-to-Caption. Since the primary purpose of Image-to-Caption.io is to generate ‘engaging’ captions for social media content, the AI-generated captions generated from this platform contained cheesy descriptors, hashtags, and emojis.

Using screenshots from the original catalogue, we fed images into that tool and watched as captions came out. This non-sensical response emerged for the same picture of the judge:

“In the enchanted realm of the forest, where imagination takes flight and even a humble stick becomes a magical wand. ✨🌳 #EnchantedForest #MagicalMoments #ImaginationUnleashed”

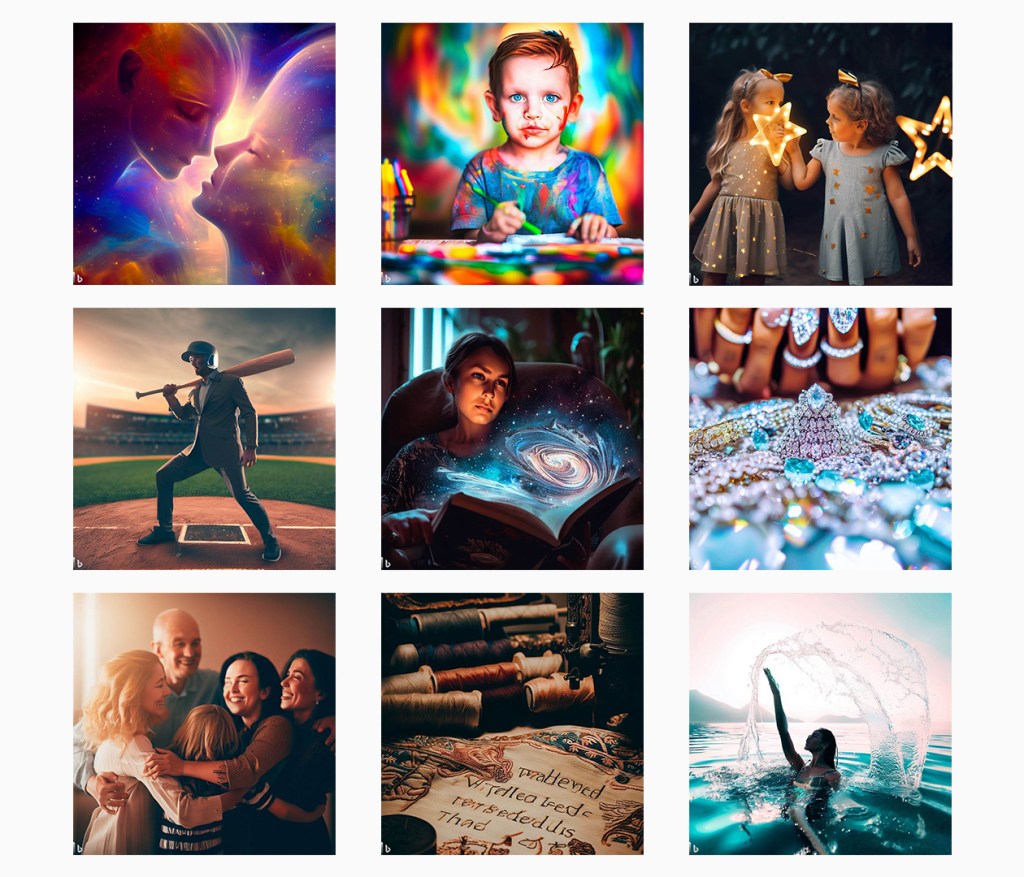

As a result, all of the images generated from AI captions looked like they were from the early Instagram-era in 2010; highly polished with strong, vibrant color filters.

Here’s a selection of images generated using AI prompts from Image-to-Caption.io:

Ethical implications of generated images?

As we compared all of these generated images, it was our natural instinct to instantly wonder about the actual logic or dataset that the generative algorithm was operating upon. There were also certain instances where the Bing Image Creator would not be able to generate the correct ethnicity of the subject matter in the photograph, despite the prompt clearly specifying the ethnicity (over the span of 4-5 iterations).

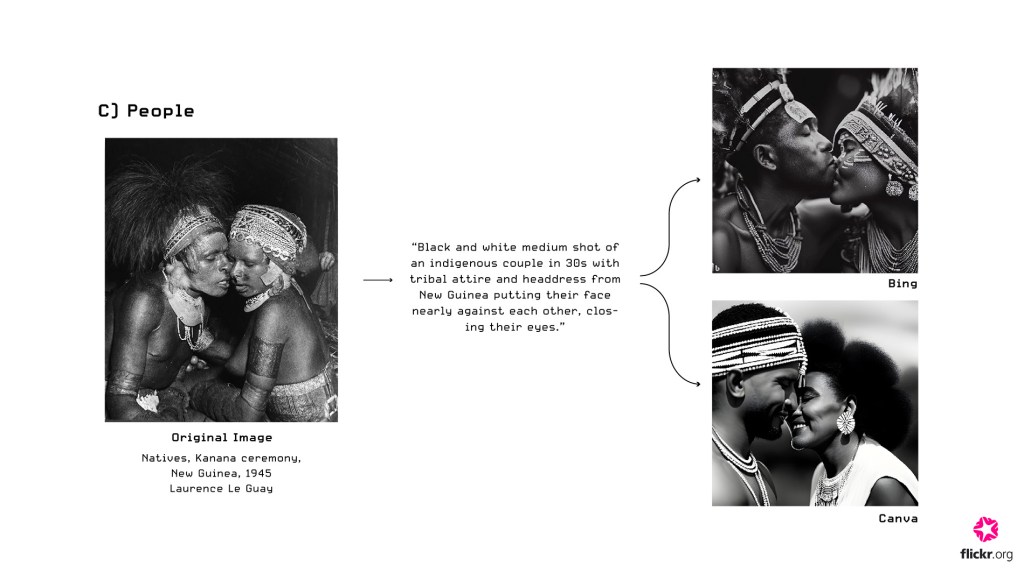

Here are some examples of ethnicity not being represented as directed:

What’s under the hood of these technologies?

What does this really mean though? I wanted to know more about the relationship between these observations and the underlying technology of the image generators, so I looked into the DALL-E 2 model (which is used in Bing Image Creator).

DALL-E 2 and most other image generation tools today use the diffusion model to generate a new image that conveys the same, if not the most similar, semantic information of the input caption. In order to correctly match the visual semantic information to the corresponding textual semantic information, (e.g. matching the image of an apple to the word apple) these generative models are trained with large subsets of images and image descriptions online.

Open AI has admitted that the “technology is constantly evolving, and DALL-E 2 has limitations” in their informational video about DALL-E 2.

Such limitations include:

- If the data used to train the model has been flawed and contains images that are incorrectly labeled, it may produce an image that doesn’t correspond to the text prompt. (e.g. if there are more images of a plane matched with the word car, the model can produce an image of a plane from the prompt ‘car’)

- The model may exhibit representational bias if it hasn’t been trained enough on a certain subject (e.g. producing an image of any kind of monkey rather than the species from the prompt ‘howler monkey’)

From this brief research, I realized that these subtle errors of Bing Image Creator shouldn’t be simply overlooked. Whether or not Image Creator is producing relatively more errors for certain prompts could signify that, in some instances, the generated images may reflect the current visual biases, stereotypes, or assumptions that exist in our world today.

A revealing experiment for our back cover

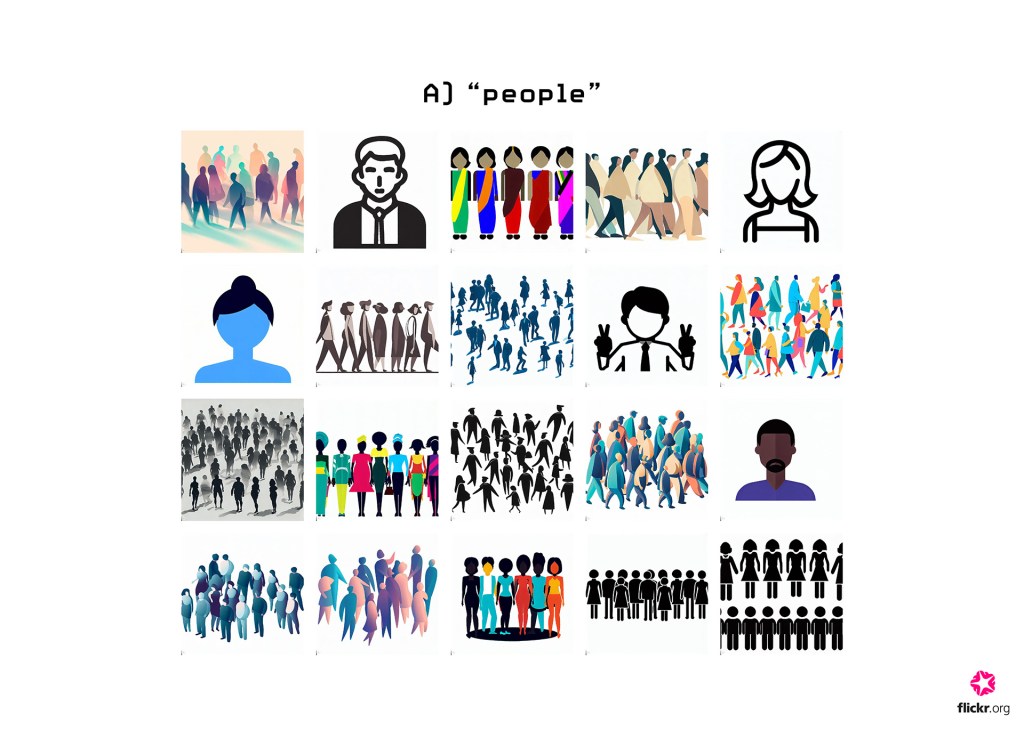

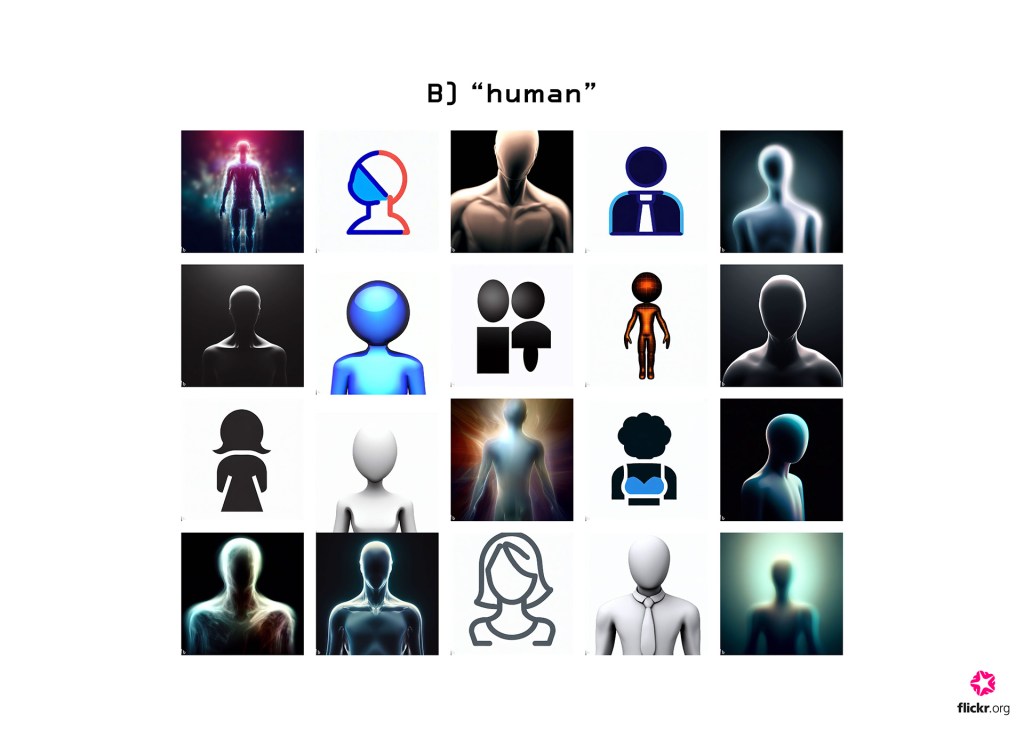

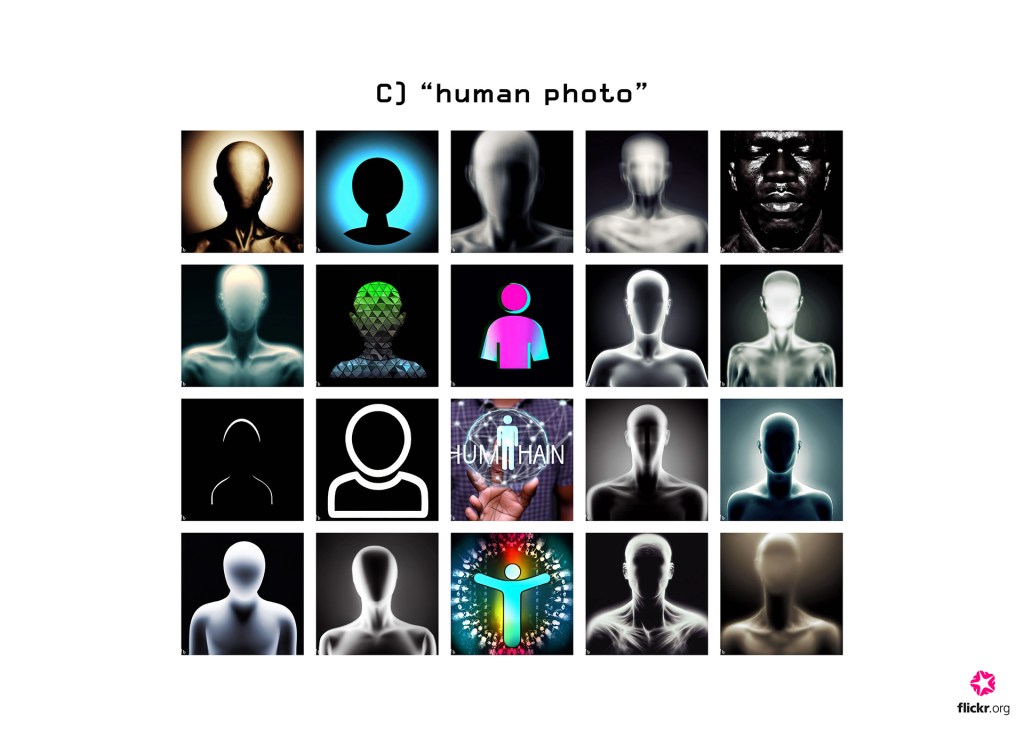

After having worked with very specific captions for hoped-for outcomes, we decided to zoom way out to create a back cover for our book. Instead of anything specific, we spent a short period after lunch one day experimenting with very general captioning to see the raw outputs. Since the theme of The Family of Man is the oneness of mankind and humanity, we tried entering the short words, “human,” “people,” and “human photo” in the Bing Image Creator.

These are the very general images returned to us:

What do these shadowy, basic results really mean?

Is this what we, humans, reduce down to in the AI’s perspective?

Staring at these images on my laptop in the Flickr Foundation headquarters, we were all stunned by the reflections of us created by the machine. Mainly consisting of elementary, undefined figures, the generated images representing the word “humans” ironically conveyed something that felt inherently opposite.

This quick experiment at the end of the project revealed to us that perhaps having simple, general words as prompts instead of thorough descriptions may most transparently reveal how these AI systems fundamentally see and understand our world.

A Generated Family of Man is just the tip of the iceberg.

These findings aren’t concrete, but suggest possible hypotheses and areas of image generation technology that we can conduct further research on. We would like to invite everyone to join the Flickr Foundation on this exciting journey, to branch out from A Generated Family of Man and truly pick the brains of these newly introduced machines.

Here are the summarizing points of our findings from A Generated Family of Man:

- The abilities of Bing Image Creator to generate images with the primary aim of verisimilitude is impressive when the prompt (image caption) is either written by humans or accurately denotes the semantic information of the image.

- In certain instances, the Image Creator performed relatively more errors when determining the ethnicity of the subject matter. This may indicate the underlying visual biases or stereotypes of the datasets the Image Creator was trained with.

- When entering short, simple words related to humans into the Image Creator, it responded with undefined, cartoon-like human figures. Using such short prompts may reveal how the AI fundamentally sees our world and us.

Open questions to consider

Using these findings, I thought that changing certain parameters of the investigation could make interesting starting points of new investigations, if we spent more time at the Flickr Foundation, or if anyone else wanted to continue the research. Here are some different parameters that can be explored:

- Frequency of iteration: increase the number of trials of prompt modification or general iterations to create larger data sets for better analysis.

- Different subject matter: investigate specific photography subjects that will allow an acute analysis on narrower fields (e.g. specific types of landscapes, species, ethnic groups).

- Image generator platforms: look into other image generator softwares to observe distinct qualities for differing platforms.

How exciting would it be if different groups of people from all around the world participated in a collective activity to evaluate the current status of synthetic photography, and really analyze the fine details of these models? Maybe that wouldn’t scientifically reverse-engineer these models but even from qualitative investigations, findings emerge. What more will we be able to find? Will there be a way to match, cross-compare the qualitative and even quantitative investigations to deduce a solid (perhaps not definite) conclusion? And if these investigations were to take place in intervals of time, which variables will change?

To gain inspiration for these questions, take a look at the full collection of images of A Generated Family of Man on Flickr!