New Grant from the Mellon Foundation!

by George OatesIt’s my great pleasure to let you know about another step forward for the Flickr Foundation today. We’ve been awarded a grant in the Public Knowledge program of the Mellon Foundation to continue our development of the Data Lifeboat. Yay!

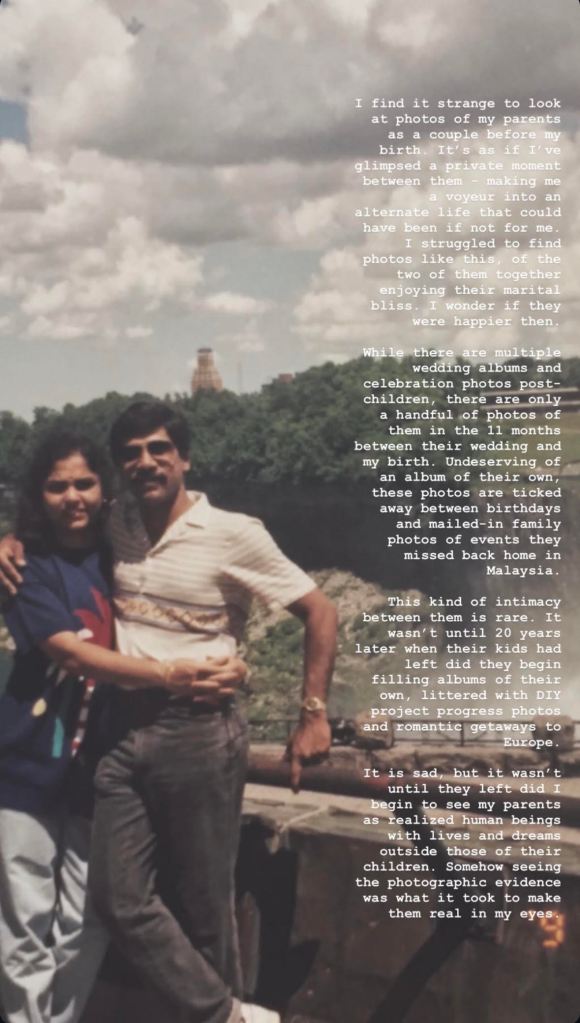

see it on flickr.com

What’s the grant for?

It’s a 12-month grant, and mostly involves using the prototype work we’ve been doing to demonstrate and discuss the concept with our community. We can’t wait to hold the two events we have planned in the (Northern hemisphere) autumn, and we’ll likely be having them on the East Coast of the USA, and in our homebase, London. If you’d like to learn more about attending one of these small meetings, please let us know via hello [at] flickr.org.

We expect to also iterate on the software itself, but we’re not quite sure where we’ll end up just yet, especially if all our conversations result in us needing to pursue different directions.

Growing the team

As part of this grant, we’ll be advertising for two new roles, likely on contract: Researcher and Software Developer. Stay tuned for those!

What’s a Data Lifeboat again?

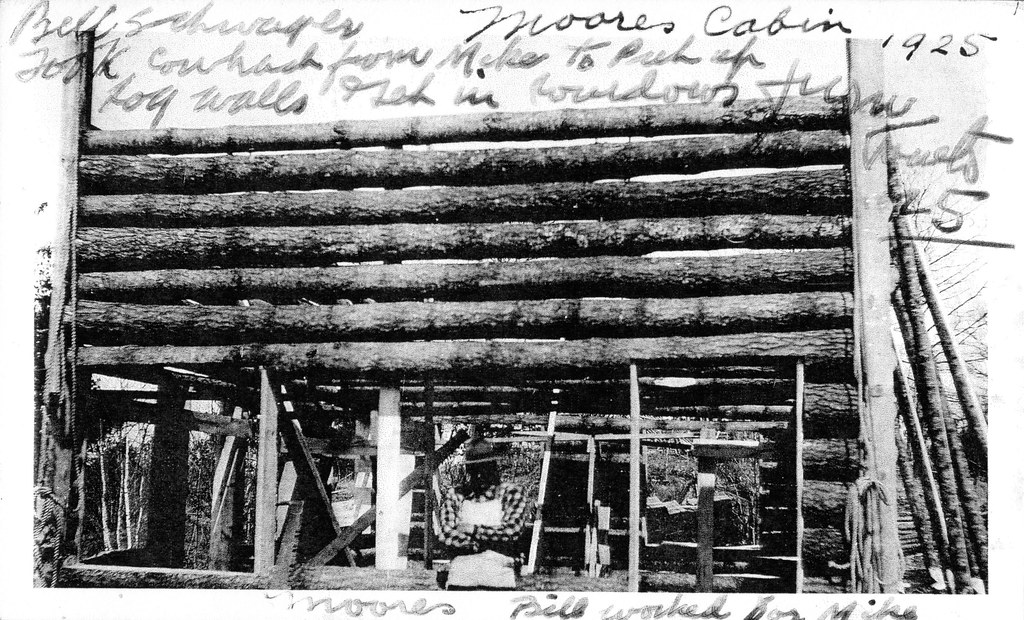

A Data Lifeboat is an archival piece of Flickr, not all of the 50 billion images and their metadata. For example, a Lifeboat might contain all the photos tagged with “sunflower” or all the Recipes to Share group submissions. Whatever facet of the data you can think of, you could generate a Data Lifeboat for it. We envision an archival sliver richer than a mere folder of JPGs: one where you can navigate the content to explore and understand its networked context. Even better, an archival sliver that is updated if things change at flickr.com.

Today, Flickr members can make an archive of their own photostream, and that works really well. You can “get your data” and that download includes most, if not all, of the kinds of information we expect a Data Lifeboat to contain. And, we want to take it two steps further, from an archival point of view:

- Allow creators to make Data Lifeboats that can contain other people’s images (with permission, and that’s very, very gnarly), and

- We plan to develop ‘known places’ for Data Lifeboats to land, so they can be registered or even accessioned as bonafide objects of meaningful cultural value. We’re calling those landing places Docks. That work is probably going to start in earnest in 2025.

In our ideal world, these docks will live inside our great and good cultural organizations, spreading the load, responsibility, and acknowledgement that our digital, user-generated cultural heritage is valuable and worthy of the attention and care our archives, museums, and libraries can provide. Jenn’s recent deeper dive into this is worth your time.

Building steadily

Our prototyping stage is nearly done now, within which we expect to come out with some Data Lifeboats to look at and critique, some “prototype policies” for Flickr members, Data Lifeboat creators, and possible “dock” operators. We are also doing some foundational work on models for sustainability, because, as you will know, to date, we’ve been largely quite bad at planning for long term life for our digital projects.

Thank you

A huge thank you to Jenn and Ewa for your fantastic support getting the grant application done, and to the team at Mellon for such constructive feedback.