Developing a New Research Method, Part 1: Photovoice, critical fabulation, and archives

by Prakash KrishnanPrakash Krishnan is a 2024 Flickr Foundation Research Fellow, working to engage community organizations with the creative possibilities afforded through archival and photo research as well as to unearth and activate some of the rich histories embedded in the Flickr archive.

I had the wonderful opportunity to visit London and Flickr Foundation HQ during the month of May 2024. The first month of my fellowship was a busy one, getting settled in, meeting the team, and making contacts around the UK to share and develop my idea for a new qualitative research method that was inspired by my perusing of just a minuscule fraction of the billions of photos uploaded and visible on Flickr.com.

Unlike the brilliant and techno-inspired minds of my Flickr Foundation cohort: George, Alex, Ewa, and Eryk, my head is often drifting in the clouds (the ones in the actual sky) or deep in books, articles, and archives. Since rediscovering Flickr and contemplating its many potential uses, I have activated my past work as a researcher, artist, and cultural worker, to reflect upon the ways Flickr could be used to engage communities in various visual and digital ethnographies.

Stemming from anthropology and the social sciences more broadly, ethnography is a branch of qualitative research involving the study of cultures, communities, or organizations. A visual ethnography thereby employs visual methods, such as photography, film, drawing, or painting.. Similarly, digital ethnography refers to the ethnographic study of cultures and communities as they interact with digital and internet technologies.

In this first post, I will trace a nonlinear timeline of different community-based and academic research projects I have conducted in recent years. Important threads from each of these projects came together to form the basis of the new ethnographic method I have developed over the course of this fellowship, which I call Archivevoice.

Visual representations of community

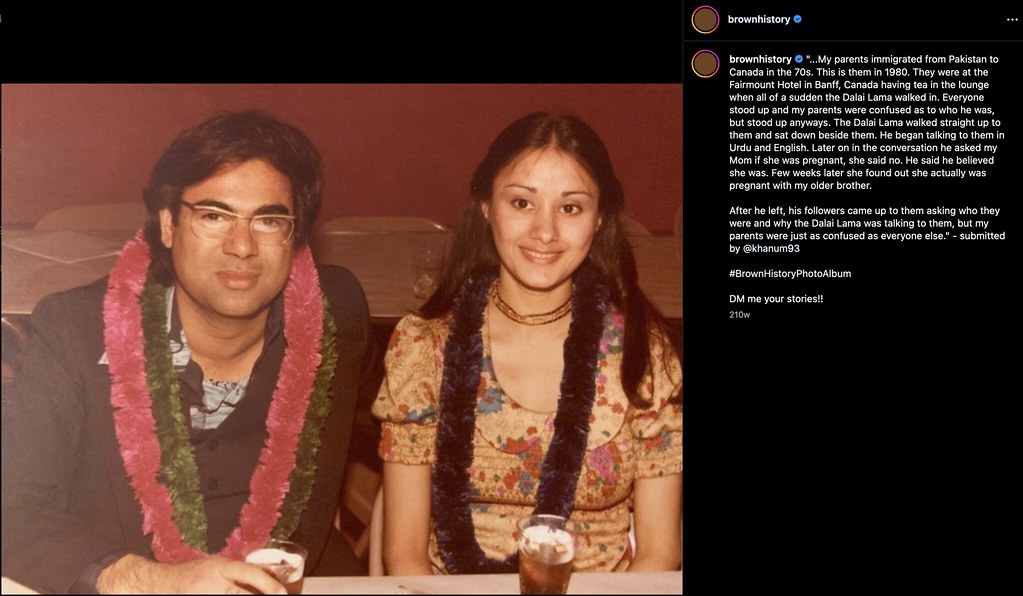

The research I conducted for my masters thesis was an example of a digital, visual ethnography. For a year, I observed Instagram accounts sharing curated South Asian visual media, analyzing the types of content they shared, the different media used, the platform affordances that were engaged with, the comments and discussions the posts incited, and how the posts reflected contemporary news, culture, and politics. I also interviewed five people whose content I had studied. Through this research I observed a strong presence of uniquely diasporic concerns and aesthetics. Many posts critiqued the idea of different nationhoods and national affiliations with the countries founded after the partition of India in 1947 – a violent division of the country resulting in mass displacement and human casualty whose effects are still felt today. Because of this violent displacement and with multiple generations of people descended from the Indian subcontinent living outside of their ancestral territory, among many within the community, I observed a rejection of nationalist identities specific to say India, Pakistan, or Bangladesh. Instead, people were using the term “South Asian” as a general catchall for communities living in the region as well as in the diaspora. Drawing from queer cultural theorist José Esteban Muñoz, I labelled this digital, cultural phenomenon I observed “digital disidentification.”[1]

My explorations of community-based visual media predate this research. In 2022, I worked with the Montreal grassroots artist collective and studio, Cyber Love Hotel, to develop a digital archive and exhibition space for 3D-scanned artworks and cultural objects called Things+Time. In 2023, we hosted a several-week-long residency program with 10 local, racialized, and queer artists. The residents were trained on archival description and tagging principles, and then selected what to archive. The objects curated and scanned in the context of this residency were in response to the overarching theme loss during the Covid-19 pandemic, in which rampant closures of queer spaces, restaurants, nightlife, music venues, and other community gathering spaces were proliferating across the city.

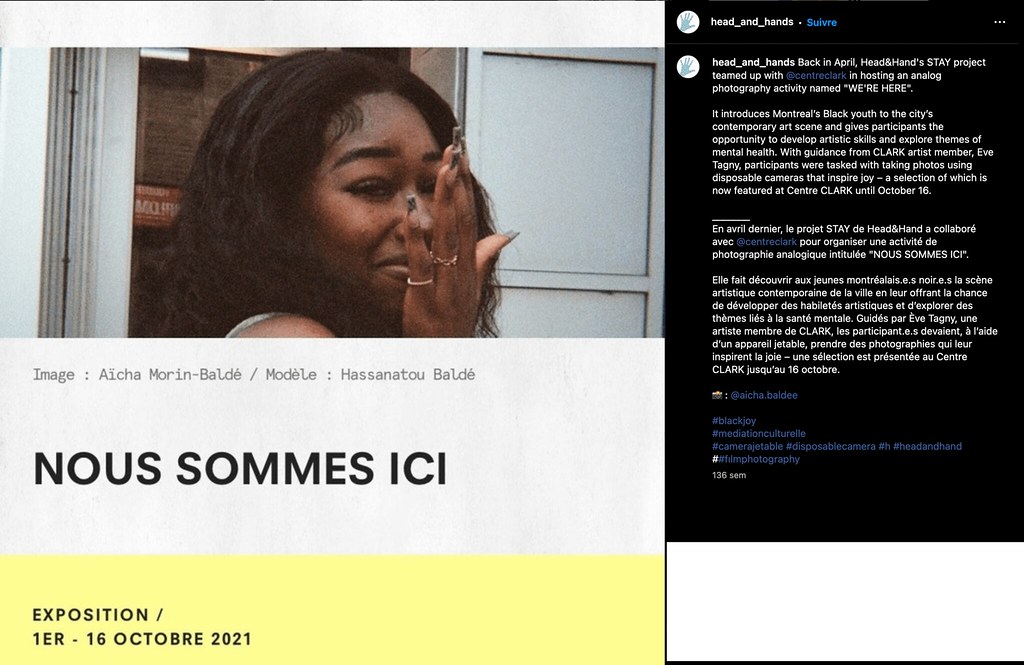

During complete pandemic lockdown, while working as the manager for cultural mediation at the contemporary gallery Centre CLARK, I conducted a similar project which involved having participants take photographs which responded to a specific prompt. In partnership with the community organization Head & Hands, I mailed disposable cameras to participants from a Black youth group whose activities were based at Head & Hands. Together with artist and CLARK member, Eve Tangy, we created educational videos on the principles of photography and disposable camera use and tasked the participants to go around their neighbourhoods taking photos of moments that, in their eyes, sparked Black Joy—the theme of the project. Following a feedback session with Eve and myself, the two preferred photos from each participants’ photo reels were printed and mounted as part of a community exhibition entitled Nous sommes ici (“We’re Here”) at the entry of Centre CLARK’s gallery.

These public community projects were not formal or academic, but, I came to understand each of these projects as examples of what is called research-creation (or practice-based research or arts-based research). Through creative methods like curating objects for digital archiving and photography, I, as the facilitator/researcher, was interested in how the media comprising each exhibition would inform myself and the greater public about the experiences of marginalized artists and Black youth at such pivotal moments in these communities.

Photovoice: Empowering research participants

The fact that both these projects involved working with a community and giving them creative control over how they wanted their research presented reminded me of the popular qualitative research method used often within the fields of public health, sociology, and anthropology called Photovoice. The method was originally coined as Photo Novella in 1992 and then later renamed Photovoice in 1996 by researchers Caroline Wang and Mary Ann Burris. The flagship study that established this method for decades involved scholars providing cameras and photography training to low-income women living in rural villages of Yunnan, China.

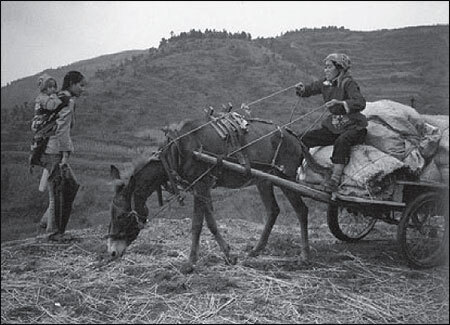

The goals of this Photovoice research were to better understand, through the perspectives of these women, the challenges they faced within their communities and societies, and to communicate these concerns to policymakers who might be more amenable to photographic representations rather than text. Citing Paulo Freire, Wang and Burris note the potential photographs have to raise consciousness and promote collective action due to their political nature. [5]

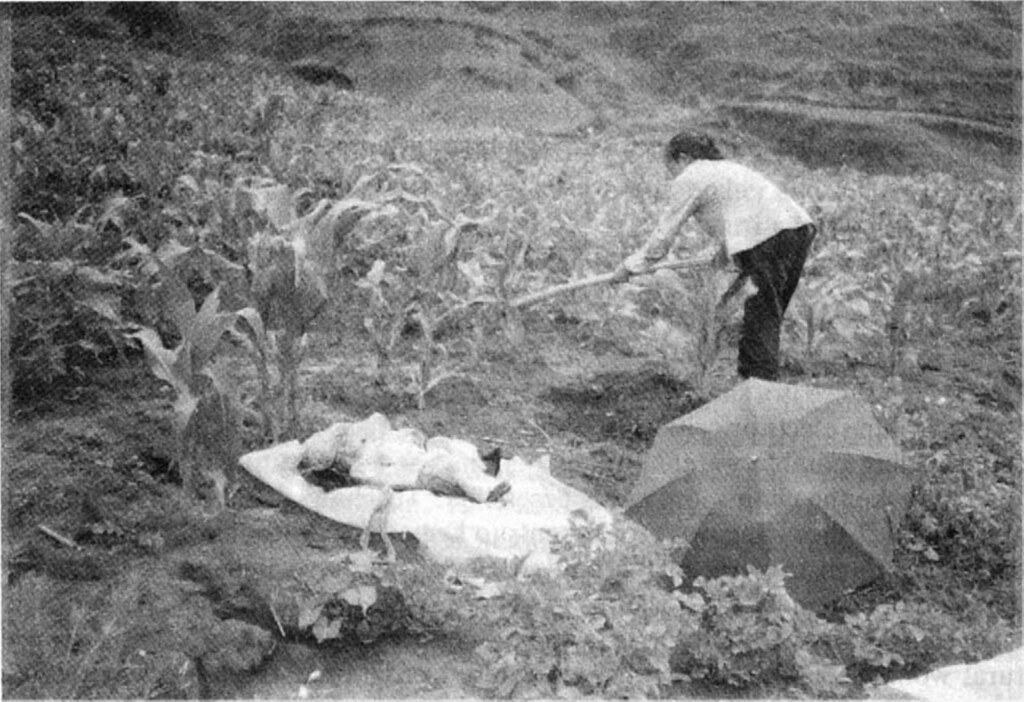

According to Wang and Burris, “these images and tales have the potential to reach generations of children to come.” [6] The images created a medium through which these women were able to share their experiences and also relate to each other. Even with 50 villages represented in the research, shared experience and strong reactions to certain photographs came up for participants – including this picture of a young child lying in a field while her mother farmed nearby.

According to the authors, “the image was virtually universal to their own experience. When families must race to finish seasonal cultivating, when their work load is heavy, and when no elders in the family can look after young ones, mothers are forced to bring their babies to the field. Dust and rain weaken the health of their infants… The photograph was a lightening [sic] rod for the women’s discussion of their burdens and needs.” [8]

Since its conception in the 1990s as a means for participatory needs assessment, many scholars and researchers have expanded Photovoice methodology. Given the exponential increase of camera access via smartphones, Photovoice is an increasingly feasible method for this kind of research. Recurring themes in Photovoice work include community health, mental health studies, ethnic and race-based studies, research with queer communities, as well as specific neighbourhood and urban studies. During the pandemic lockdowns, there were also Photovoice studies conducted entirely online, thus giving rise to the method of virtual Photovoice. [9]

Critical Fabulation: Filling the gaps in visual history

Following my masters thesis research, I became more interested in how communities sought to represent themselves through photography and digital media. Not only that, but also how communities would form and engage with content circulated on social media – despite these people not being the originators of this content.

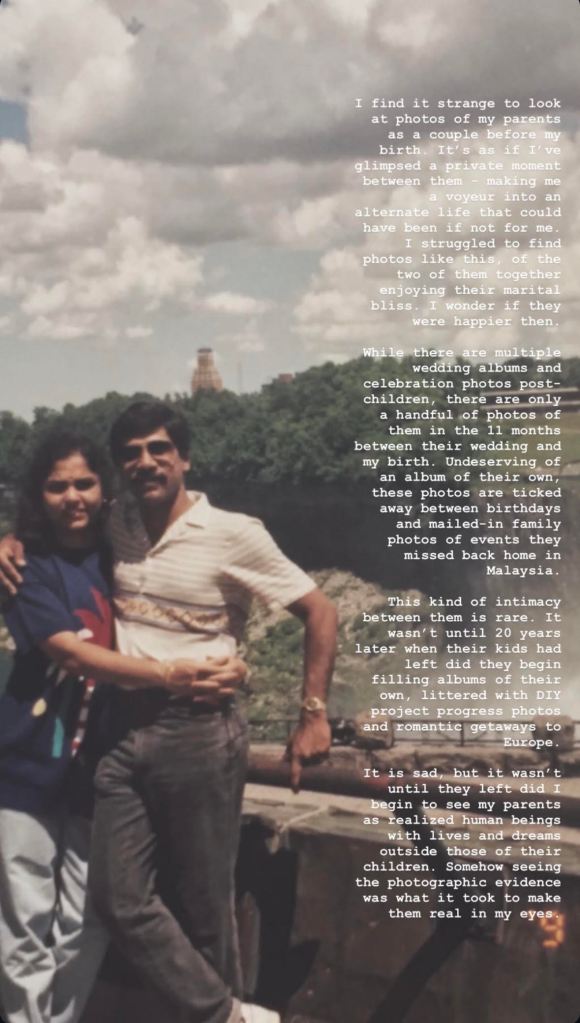

In my research, people reacted most strongly to family photographs depicting migration from South Asia to the Global North. Although reasons for emigration varied across the respondents, many people faced similar challenges with the immigration process and resettlement in a new territory. They shared their experiences through commenting online.

People in communities which are underrepresented in traditional archives are often forced to work with limited documentation. They must do the critical and imaginative work of extrapolating what they find. While photographs can convey biographical, political, or historical meaning, exploring archived images with imagination can foster creative interpretation to fill gaps in the archival record. Scholar of African-American studies, Saidiya Hartman, introduced the term “critical fabulation” to denote this practice of reimagining the sequences of events and actors behind the narratives contained within the archive. In her words, this reconfiguration of story elements, attempts “to jeopardize the status of the event, to displace the received or authorized account, and to imagine what might have happened or might have been said or might have been done.” [10] In reference to depictions of narratives from the Atlantic slave trade in which enslaved people are often referred to as commodities, Hartman writes “the intent of this practice is not to give voice to the slave, but rather to imagine what cannot be verified, a realm of experience which is situated between two zones of death—social and corporeal death—and to reckon with the precarious lives which are visible only in the moment of their disappearance. It is an impossible writing which attempts to say that which resists being said (since dead girls are unable to speak). It is a history of an unrecoverable past; it is a narrative of what might have been or could have been; it is a history written with and against the archive.” [11]

I am investigating what it means to imagine the unverifiable and reckoning what only becomes visible at its disappearance. In 2020, I wrote about Facebook pages serving as archives of queer life in my home town, Montreal. [12] For this study, I once again conducted a digital ethnography, this time of the event pages surrounding a QTPOC (queer/trans person of colour)-led event series known as Gender B(l)ender. Drawing from Sam McBean, I argued that simply having access to these event pages on Facebook creates a space of possibility in which one can imagine themselves as part of these events, as part of these communities – even when physical, in-person participation is not possible. Although critical fabulation was not a method used in this study, it seemed like a precursor to this concept of collectively rethinking, reformulating, and resurrecting untold, unknown, or forgetting histories of the archives. This finally leads us to the project of my fellowship here at the Flickr Foundation.

In addition to this fellowship, I am coordinator of the Access in the Making Lab, a university research lab working broadly on issues of critical disability studies, accessibility, anti-colonialism, and environmental humanities. In my work, I am increasingly preoccupied with the question of methods: 1) how do we do archival research—especially ethical archival research—with historically marginalized communities; and, 2) how can research “subjects” be empowered to become seen as co-producers of research.

I trace this convoluted genealogy of my own fragmented research and community projects to explain the method I am developing and have proposed to university researchers as a part of my fellowship. Following my work on Facebook and Instagram, I similarly position Flickr as a participatory archive, made by millions of people in millions of communities. [13] Eryk Salvaggio, fellow 2024 Flickr Foundation research fellow, also positions Flickr as an archive such that it “holds digital copies of historical artifacts for individual reflection and context.” [14] From this theoretical groundwork of seeing these online social image/media repositories as archives, I seek to position archival items – i.e. the photos uploaded to Flickr.com – as a medium for creative interpretation by which researchers could better understand the lived realities of different communities, just like the Photovoice researchers. I am calling this set of work and use cases “Archivevoice”.

In part two of this series, I will explore the methodology itself in more detail including a guide for researchers interested in engaging with this method.

Footnotes

[1] Prakash Krishnan, “Digital Disidentifications: A Case Study of South Asian Instagram Community Archives,” in The Politics and Poetics of Indian Digital Diasporas: From Desi to Brown (Routledge, 2024), https://www.routledge.com/The-Politics-and-Poetics-of-Indian-Digital-Diasporas-From-Desi-to-Brown/Jiwani-Tremblay-Bhatia/p/book/9781032593531.

[2] Caroline Wang and Mary Ann Burris, “Empowerment through Photo Novella: Portraits of Participation,” Health Education Quarterly 21, no. 2 (1994): 171–86.

[3] Kunyi Wu, Visual Voices, 100 Photographs of Village China by the Women of Yunnan Province, 1995.

[4] Wu.

[5] Caroline Wang and Mary Ann Burris, “Photovoice: Concept, Methodology, and Use for Participatory Needs Assessment,” Health Education & Behavior 24, no. 3 (1997): 384.

[6] Wang and Burris, “Empowerment through Photo Novella,” 179.

[7] Wang and Burris, “Empowerment through Photo Novella.”

[8] Wang and Burris, 180.

[9] John L. Oliffe et al., “The Case for and Against Doing Virtual Photovoice,” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 22 (March 1, 2023): 16094069231190564, https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069231190564.

[10] Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (2008): 11.

[11] Hartman, 12.

[12] Prakash Krishnan and Stefanie Duguay, “From ‘Interested’ to Showing Up: Investigating Digital Media’s Role in Montréal-Based LGBTQ Social Organizing,” Canadian Journal of Communication 45, no. 4 (December 8, 2020): 525–44, https://doi.org/10.22230/cjc.2020v44n4a3694.

[13] Isto Huvila, “Participatory Archive: Towards Decentralised Curation, Radical User Orientation, and Broader Contextualisation of Records Management,” Archival Science 8, no. 1 (March 1, 2008): 15–36, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-008-9071-0.

[14] Eryk Salvaggio, “The Ghost Stays in the Picture, Part 1: Archives, Datasets, and Infrastructures,” Flickr Foundation (blog), May 29, 2024, https://www.flickr.org/the-ghost-stays-in-the-picture-part-1-archives-datasets-and-infrastructures/.

Bibliography

Hartman, Saidiya. “Venus in Two Acts.” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (2008): 1–14.

Huvila, Isto. “Participatory Archive: Towards Decentralised Curation, Radical User Orientation, and Broader Contextualisation of Records Management.” Archival Science 8, no. 1 (March 1, 2008): 15–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-008-9071-0.

Krishnan, Prakash. “Digital Disidentifications: A Case Study of South Asian Instagram Community Archives.” In The Politics and Poetics of Indian Digital Diasporas: From Desi to Brown. Routledge, 2024. https://www.routledge.com/The-Politics-and-Poetics-of-Indian-Digital-Diasporas-From-Desi-to-Brown/Jiwani-Tremblay-Bhatia/p/book/9781032593531.

Krishnan, Prakash, and Stefanie Duguay. “From ‘Interested’ to Showing Up: Investigating Digital Media’s Role in Montréal-Based LGBTQ Social Organizing.” Canadian Journal of Communication 45, no. 4 (December 8, 2020): 525–44. https://doi.org/10.22230/cjc.2020v44n4a3694.

Oliffe, John L., Nina Gao, Mary T. Kelly, Calvin C. Fernandez, Hooman Salavati, Matthew Sha, Zac E. Seidler, and Simon M. Rice. “The Case for and Against Doing Virtual Photovoice.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 22 (March 1, 2023): 16094069231190564. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069231190564.

Salvaggio, Eryk. “The Ghost Stays in the Picture, Part 1: Archives, Datasets, and Infrastructures.” Flickr Foundation (blog), May 29, 2024. https://www.flickr.org/the-ghost-stays-in-the-picture-part-1-archives-datasets-and-infrastructures/.

Wang, Caroline, and Mary Ann Burris. “Empowerment through Photo Novella: Portraits of Participation.” Health Education Quarterly 21, no. 2 (1994): 171–86.

———. “Photovoice: Concept, Methodology, and Use for Participatory Needs Assessment.” Health Education & Behavior 24, no. 3 (1997): 369–87.

Wu, Kunyi. Visual Voices, 100 Photographs of Village China by the Women of Yunnan Province, 1995.