Introducing Prakash Krishnan, 2024 Research Fellow

Prakash Krishnan (he/him) is an artist-researcher and cultural worker based in Tiohtià:ke (Montréal, Canada) on the stolen lands of the Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) Nation. His recent projects explore various issues relating to accessibility and disability justice, community archival practices, and environmental humanities. He is joining the Flickr Foundation as a research fellow from May to July 2024.

What’s drawn you to family archives?

For a class on research-creation methods (also referred to as arts-based research) I took in 2019, I had big ambitions of creating an experimental, non-narrative documentary using cellphone footage during a planned trip to my parents’ home country of Malaysia. Upon returning home and examining the footage, I unfortunately came to the realization that a combination of obsolete technology (an iPhone 4S in the year of the iPhone 11 – imagine!!!), corrupted sound, and sabotage by my own, unsteady hands rendered my footage unusable. Scrambling to find some way to complete my term project in the final weeks of the semester, I decided to undergo what I saw as an intrapersonal reflection via an investigation of my own family archives.

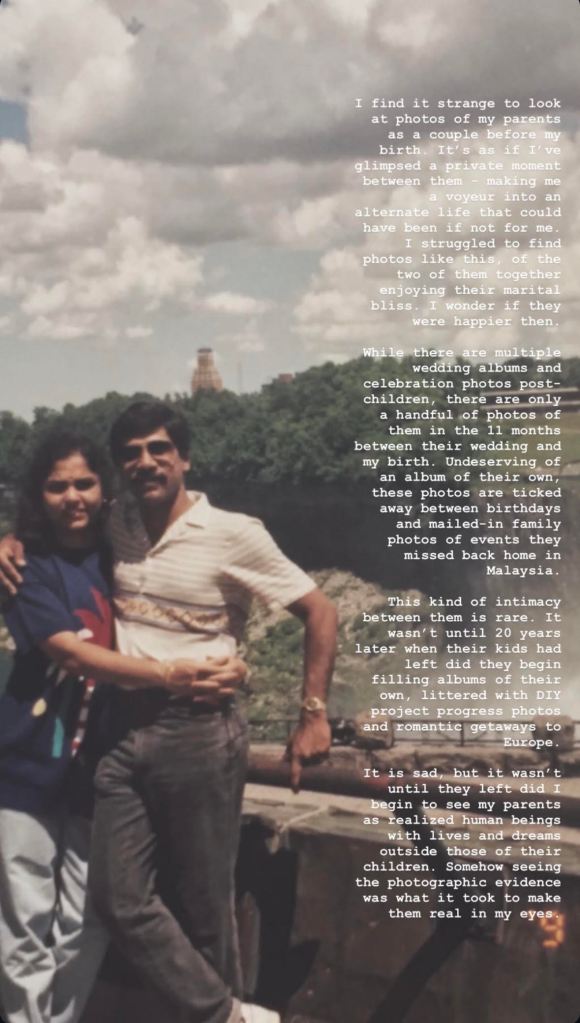

These “archives” are fairly small. Limited to the albums of photos my parents once carefully categorized and now just haphazardly store in a pile on a basement shelf. I confess that when living with my parents as a child, I was too self-centred to pay attention to any of the albums that didn’t include me. As the firstborn and only a year after my parents’ marriage, effectively I was prominently featured in all the albums except one. Paging through the album documenting my parents’ courtship, wedding, and first year of marriage, I was embarrassed by my shock of confronting these two people, whom I’ve evidently known my whole life, living this whole other life without me. As I passed on to the albums of my infancy, I became overcome with emotion seeing them making their life together, still virtually strangers having had an arranged marriage and finding themselves shortly thereafter in a new country, facing what I know now as the pressures that come with being not only new parents, but new immigrants, newly coupled, and struggling with finding lasting employment.

Inspired by my reaction to these albums, I planned on conducting an oral history interview with my parents. I wanted to know the people in these photos, what they were thinking, feeling, doing. Yet there was something holding me back. The photos were so intimate, often only one of them in the shot, as the other was behind the camera. These felt like private moments between the two of them that was solely theirs to wholly know and experience. Instead, I took a selection of these photos and wrote my own reflections. Searching back through my own memories of the rare times my parents spoke about their youth and the early years of their marriage, I pieced together a history of their early settlement and parenthood in Canada (circa 1991-1995) through written reflections and image descriptions I then inscribed on the digitized copies of the photos. I’m usually not a very emotionally expressive person, but I cried when I presented this to my class.

This experience fundamentally changed my relationship to photo archives and sowed the seeds for what would become my master’s thesis South Asian Instagram Community Archives: A Platform for Performance, Curation, and Identity as well as my approach to creative and poetic visual description for blind and low-vision communities as workshopped in the online exhibitions Audio Description in the Making and Air, River, Sea, Soil: A History of an Exploited Land.

Continuing this line of engagement along with my community archival engagement approaches prototyped in the community digital archive/exhibition project Things+Time,

What would you like to work on during your fellowship?

I will, over the course of my fellowship at the Flickr Foundation, work with two community organizations, one based in London, UK and one in Montreal, Canada to undergo a digital archival excavation workshop. Through a series of guided prompts and reflections, these community groups will decide specific search criteria in order to activate the Flickr archive, creating informal collections that respond to and inform the earlier reflections. Together, community members will create descriptions for the images that can dually serve as archival and visual descriptions for potential use in a future exhibition.

Using a “photovoice” methodology, participants will also be tasked with adding their own, related and annotated material to the Flickr archive in response to the collective and reflections feedback from the workshop.

The goals of this project are to engage community organizations with the creative possibilities afforded through archival and photo research as well as to unearth and activate some of the rich histories embedded in the Flickr archive.