A conversation between Tosin Adeosun, Founder of African Style Archive, and the Foundation’s Research Lead, Fattori McKenna. They discuss the complexities of digital-first collecting, how cultural politics shapes non-institutional archives and some African fashion gems hidden on Flickr.com

Tell us, what was the impetus behind African Style Archive?

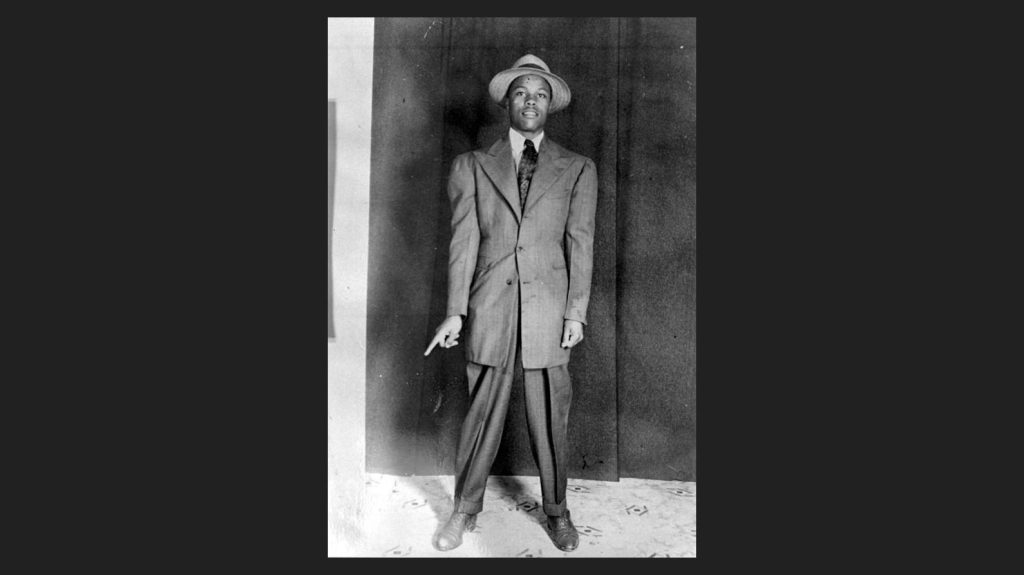

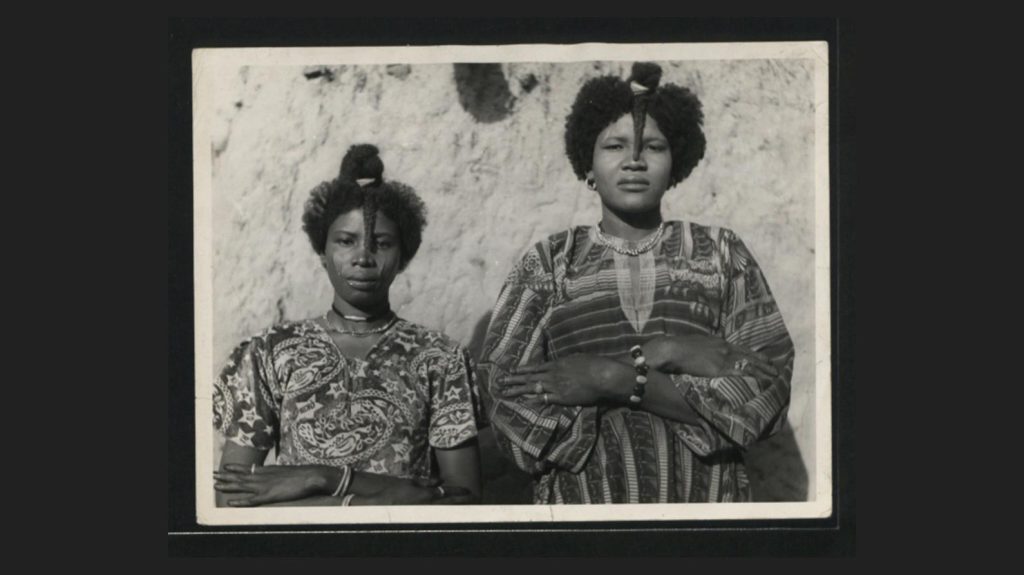

African Style Archive was born out of necessity, a way to research and document African fashion history and sartorial references to share with a wider audience. Photography was my entry point, as I’ve always been drawn to the medium and the stories it holds. While reviewing my family’s archival photographs and record sleeve collection in Ibadan, Nigeria, I became obsessed with the stylish people immortalised in those images. That curiosity led me to explore how fashion and history intersect in African and diasporic contexts.

At the time, I had just completed my MA in Art History and Museum Curating with Photography at the University of Sussex. My dissertation focused on photographs from the Black Cultural Archive in Brixton, uncovering links between fashion and self-representation in the Black British community. I wanted to continue that research beyond academia.

The platform officially began on Instagram in 2020, just before the pandemic, as a way to share my findings and contextualise the photographs I was discovering, especially the work of African photographers and their sitters. Instagram made sense, it was visual, concise, and had a wide reach. Since then, African Style Archive has grown into an educational platform with collaborations across brands and institutions such as Byredo, Labrum London, Ahluwalia, International Curators Forum, Lighthouse among others.

Given your sourcing from far-and-wide, have you discovered any exciting collections on Flickr.com?

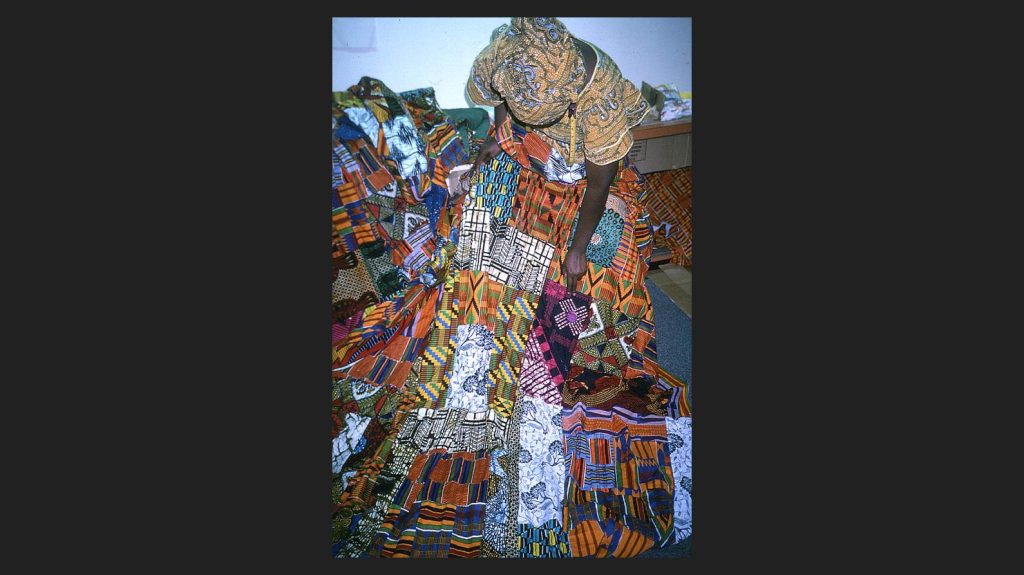

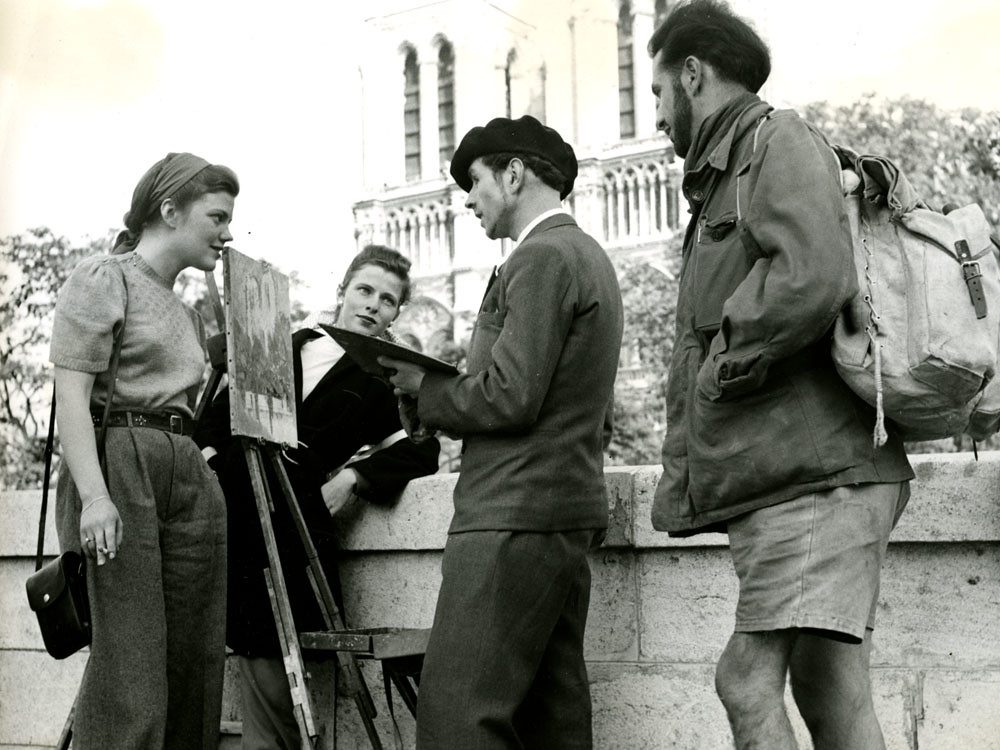

One of the first collections I came across, long before I knew about the Flickr Foundation, was by a user named Tommy Miles. He had photographed and documented an incredible archive of commemorative wax-print fabrics from his personal pagne collection. Some of the textiles date back to the 1960s, and I remember feeling like I’d struck gold when a deep Google search led me to his album hosted on Flickr.

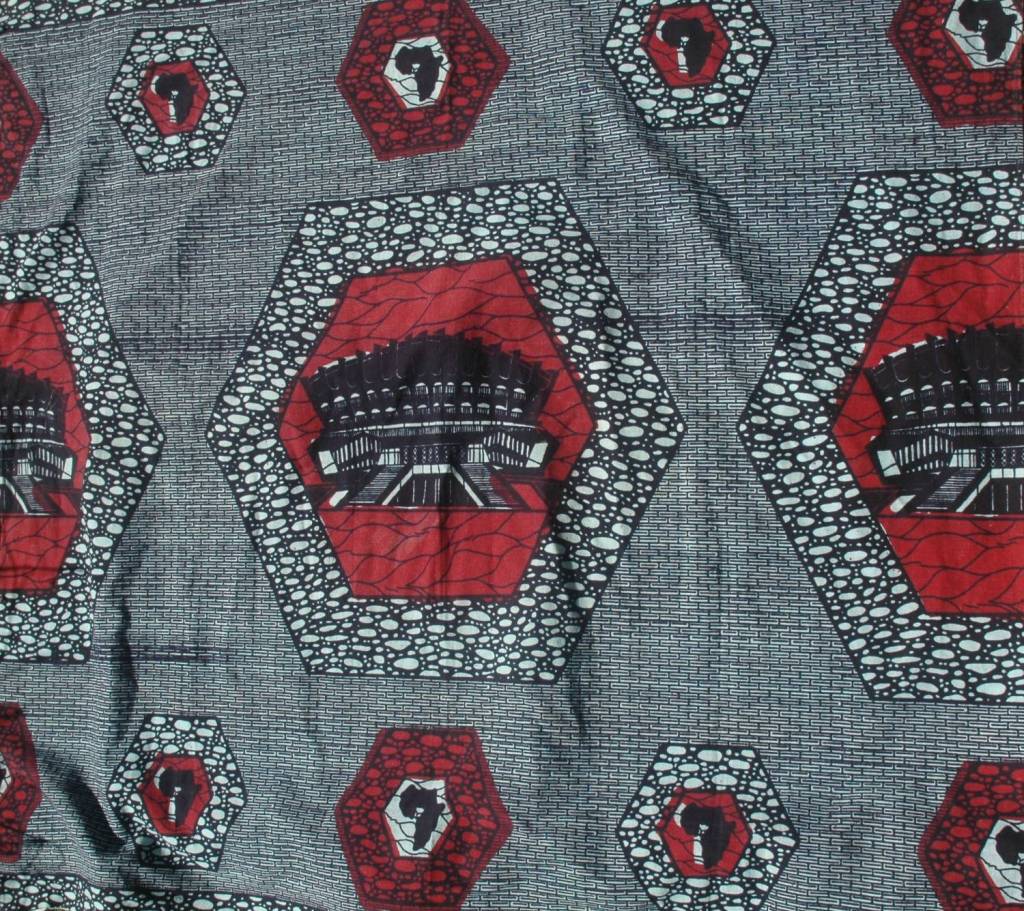

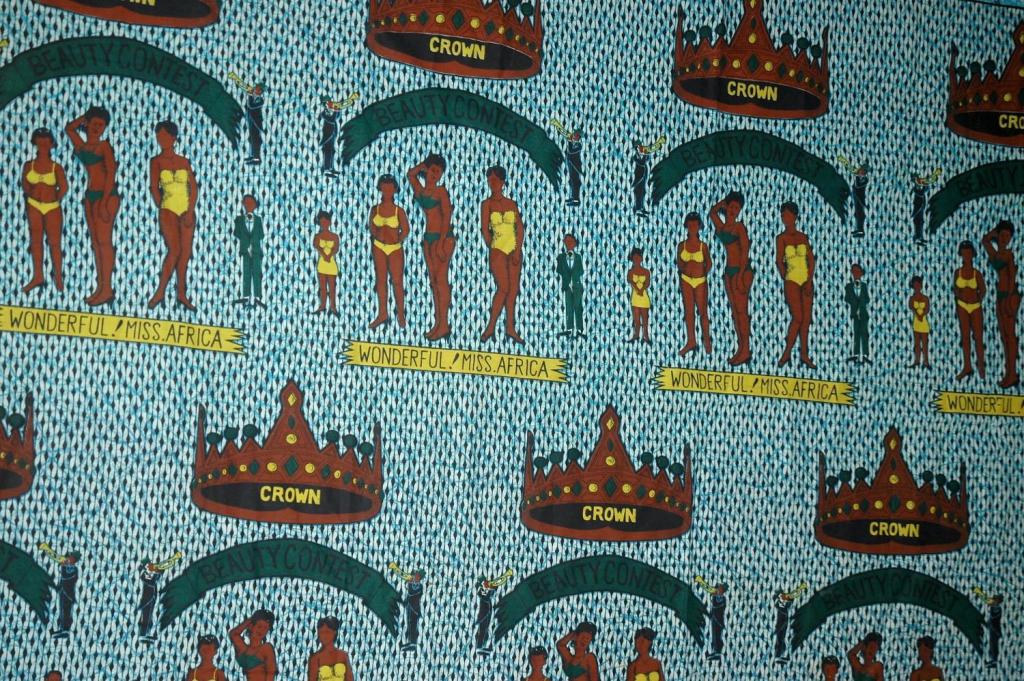

That collection became instrumental in my research into African commemorative cloth—its symbolism, function, and cultural significance. One standout was the Miss Africa wax-print cloth, beautifully documented with extensive metadata about its origins. Another was a cloth featuring the Nigerian National Theatre, which may have been produced around the time of FESTAC ’77, the landmark Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture held in Lagos in 1977.

I’m not sure if museums currently hold these particular fabrics in their collections, but discovering them on Flickr was exciting, Tommy Miles has done excellent work in archiving these important fabrics. It was encouraging to see such thoughtful documentation and preservation being done independently. You can read more about the collection on his personal website here.

Explore some of Tosin’s favourites from Flickr and Flickr Commons below:

Can you walk us through your approach to curation and collecting?

My process is a mix of instinct and structure, often led by a feeling or curiosity. I’m always thinking and researching, even subconsciously when I’m meant to be resting. As research in this field is still emerging, I have to be both creative and intentional in how I curate and collect.

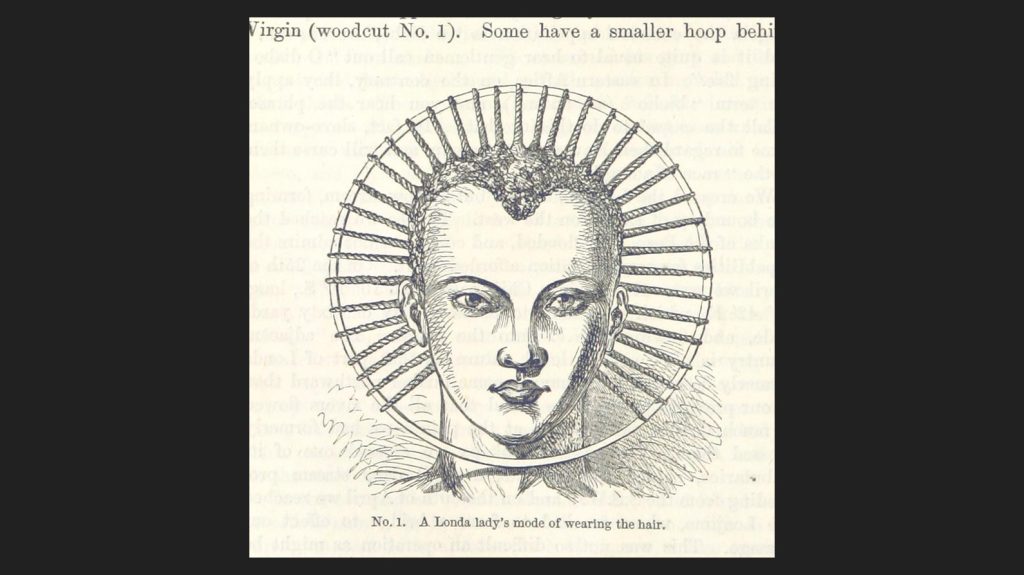

I look across many mediums, not just photography. I research through magazines, books, films, music videos, and documentation of political or cultural moments. Sometimes a fabric, figure, or movement catches my attention and I start tracing its story. For example, if I’m drawn to East African textiles, I’ll look into their production and significance, and also seek out images of people wearing them, designers who use them, or artists who reference them in their work. It becomes an ecosystem, piecing together fragments to form a fuller narrative.

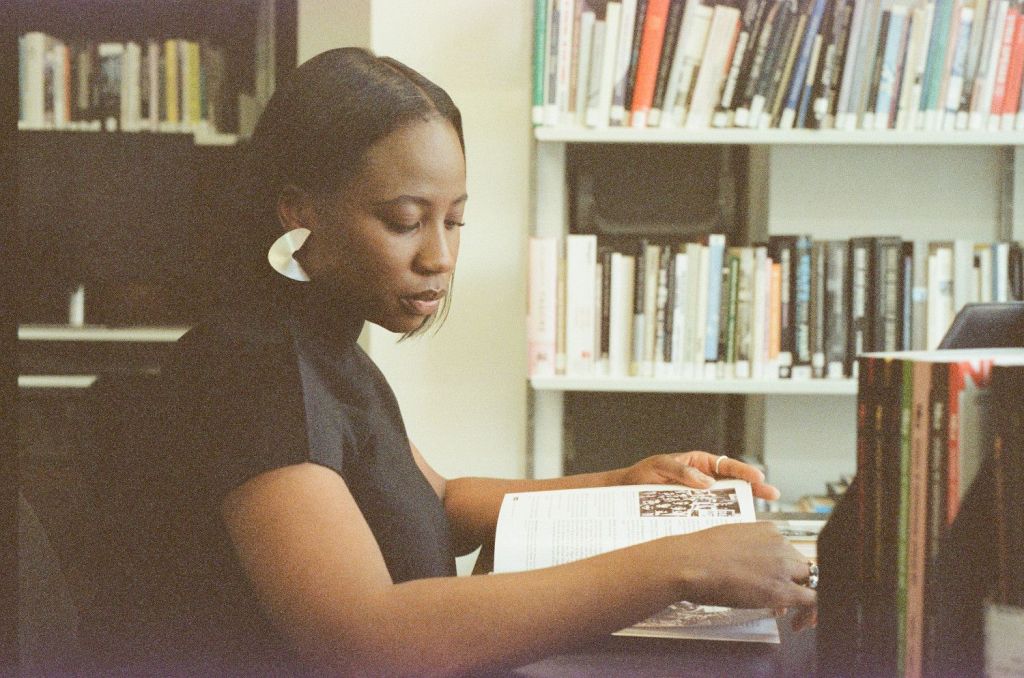

Digitally, I’ve been fortunate to build relationships with photographers and estates who generously allow me to share their work, so that part of the collection continues to grow through trust and collaboration. Offline, I’ve been building a physical reference library of books, magazines, and ephemera focused on African fashion history through design, photography, memoir, and art. I currently have over 80 books and keep an organised system for tracking what I own and what I’m still looking for. It’s always evolving.

How have you been thinking about the ethics of contemporary curating when handling archival materials?

Ethics are always front of mind in my curatorial work, especially when dealing with historical or personal photographs. In the digital realm, the lines can be even more blurred, so I’m intentional about consent, context, and credit. I think a lot about what it means to represent people whose stories might have been previously overlooked or flattened, and how to do so with care and depth.

There are cultural and political considerations at every turn, from resisting extractive storytelling, to challenging whose histories get preserved and why. With user-generated photography, I treat it the same way I do archival material, with respect, curiosity, and a responsibility to amplify rather than distort.

The internet is awash with images, but these are often poorly described. How do you deal with missing metadata in the images you source?

In the early days, I sourced images online, especially during the pandemic when physical access to archives, studios, and libraries was restricted. But over time, sadly, I noticed it was often the same pool of images circulating. This led me to go deeper, into old blogs from the 2000s and lesser-known platforms, but even then, image quality was sometimes poor and many photographs lacked credits, context, or provenance.

When images lack provenance or credits, it’s not just missing information but also a form of erasure. Fashion is tied to identity and memory, and without knowing who made, wore, or photographed the people and the clothes worn, we lose vital connections to people and histories already underrepresented in archives. Including the right metadata doesn’t only ensure accuracy, it also affirms authorship and preserves cultural heritage.

I also always try to credit images properly and follow copyright guidance, so if I come across orphaned images with no traceable photographer or source, I usually don’t include them. That said, when an image feels particularly significant, I’ll dig deeper to investigate its origins – the community of people that engage with the archive are also brilliant. I’ve had people share information about photographers in the past when I might not have known who captured the image. Sometimes I’m able to bridge the metadata gaps, sometimes not. That’s part of the beauty and the frustration of curating in the digital age.

In your experience, what has been the value of user-generated photography in African Style Archive?

User-generated photography opens up new possibilities for digital preservation. Social media as a tool for archiving and storytelling creates a wider, more accessible platform, beyond what many imagined a decade ago. It has allowed independent researchers and archivists like myself to curate outside of institutional walls and to offer different perspectives without gatekeeping or rigid frameworks.

Through African Style Archive, I’ve connected with a wide network of people, practitioners, and organisations who are just as invested in this work. That kind of reach and exchange wouldn’t be possible without the digital and user-generated elements of the project.

We’re excited to know more… Could you give us a sneak peak into the African Style Archive ecosystem you’re building?

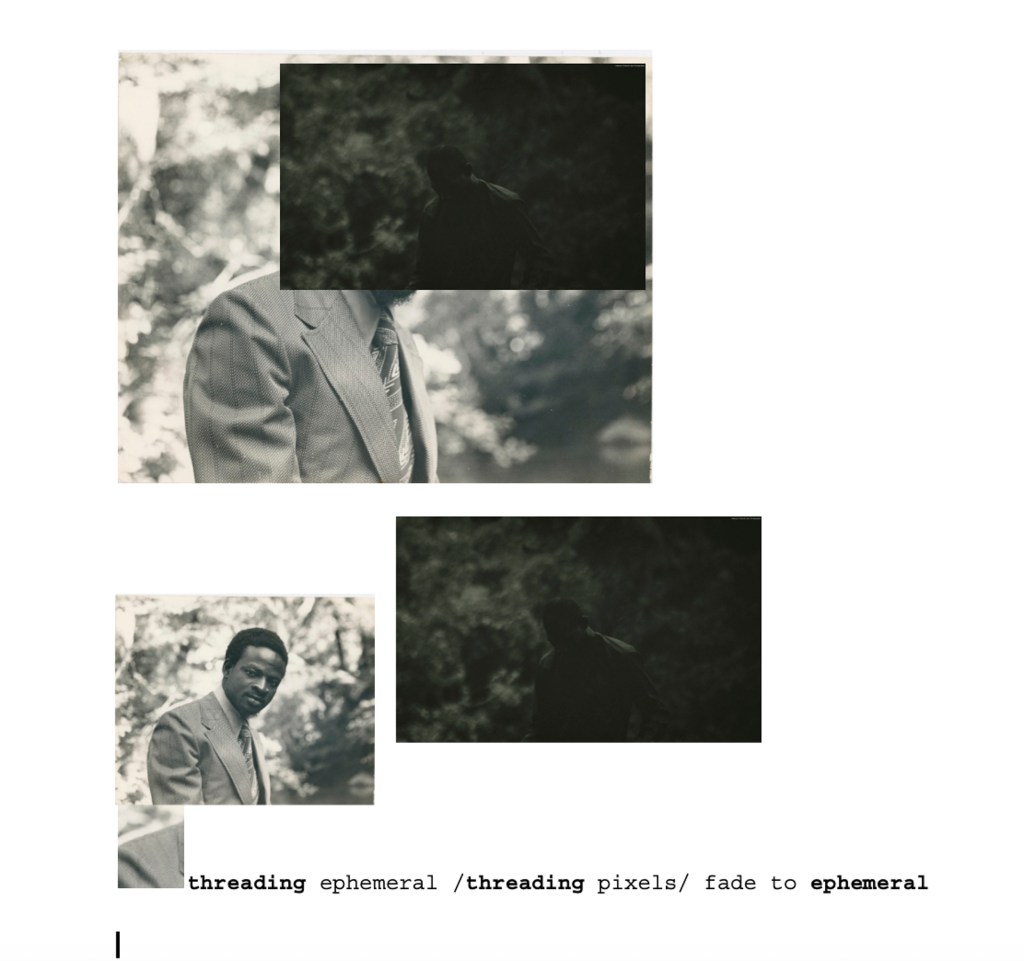

I’m always thinking about how to grow the work, it’s a constant creative challenge – though it is very exciting and I am fortunate to feel so inspired by my practice and archiving. Right now, I’m building a digital archive that feels both functional and tactile, something that evokes the experience of flipping through archival magazines and photography archives or discovering ephemera, but online. I want it to be a space for storytelling, learning, and layered discovery.

This new phase will expand the ecosystem of African Style Archive, allowing for deeper exploration of photography, moving images, fashion, and design. It will also support new editorial features that bring together history, aesthetics, and education, all central to the platform’s mission.

Offline, I’m developing physical spaces for shared learning, through the photobooks, rare magazines, and images I’ve been collecting. I’ve experimented with a mobile library, and I’m thinking more about workshops and experiences that explore what it means to archive sartorial history and visual culture in real time.

—

You can keep up to date with Tosin’s work here @africanstylearchive and www.tosinadeosun.com