Design students, Juwon Jung and Maya Osaka, the inaugural cohort of Flickr Foundation’s New Curators program, embarked on a journey exploring what happens when you interface synthetic image production with historic archives.

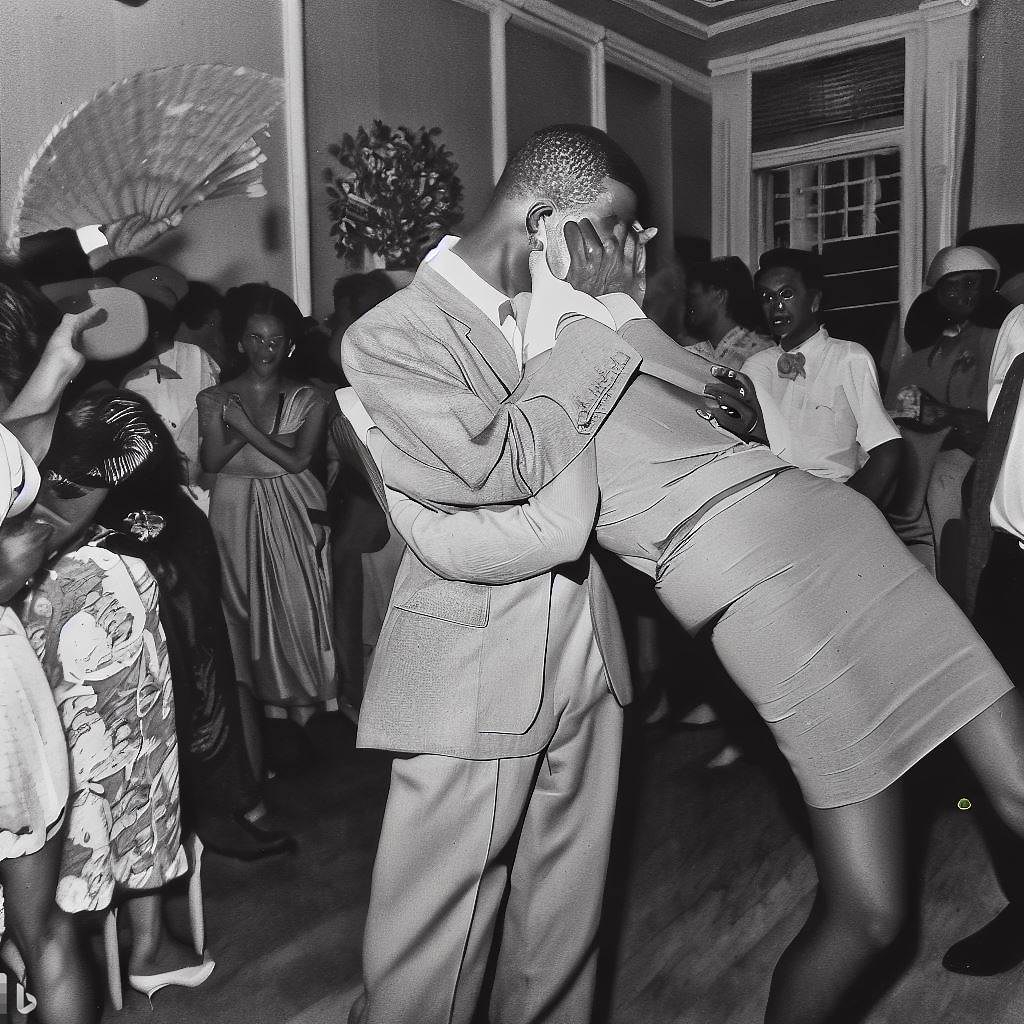

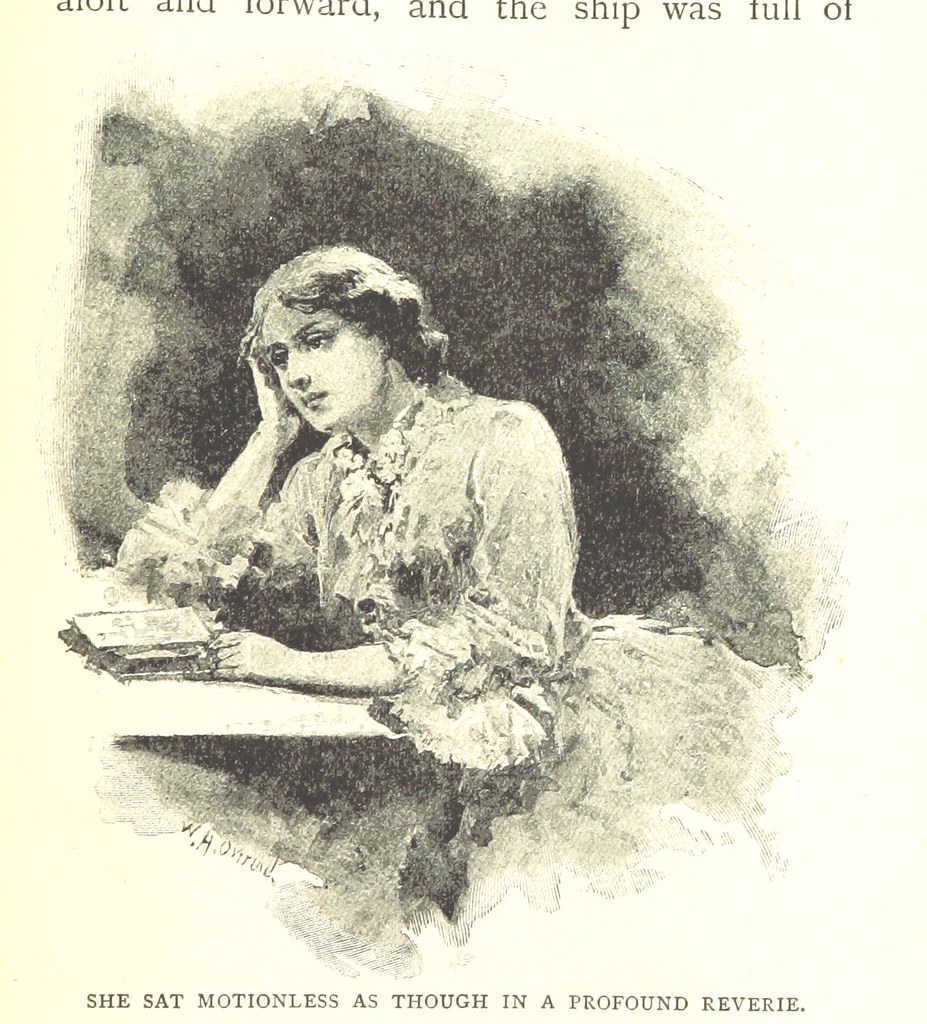

This blog post marks the release of Flickr Foundation’s A Generated Family of Man, the third iteration in a series of reinterpretations of the 1955 MoMA photography exhibition, The Family of Man.

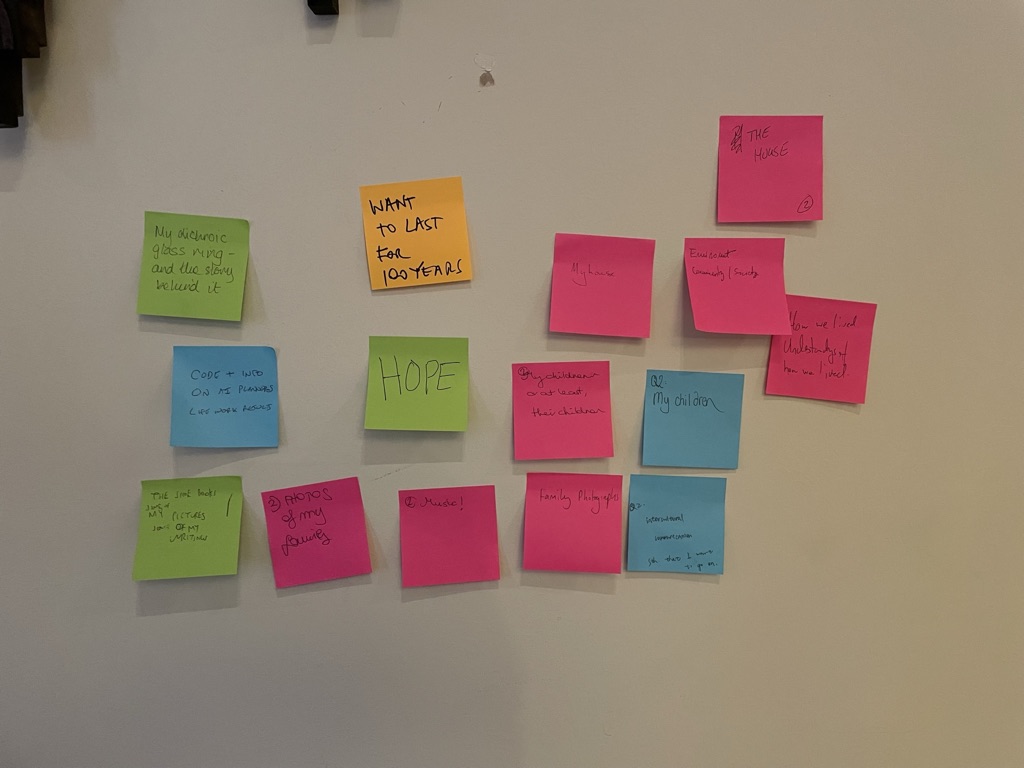

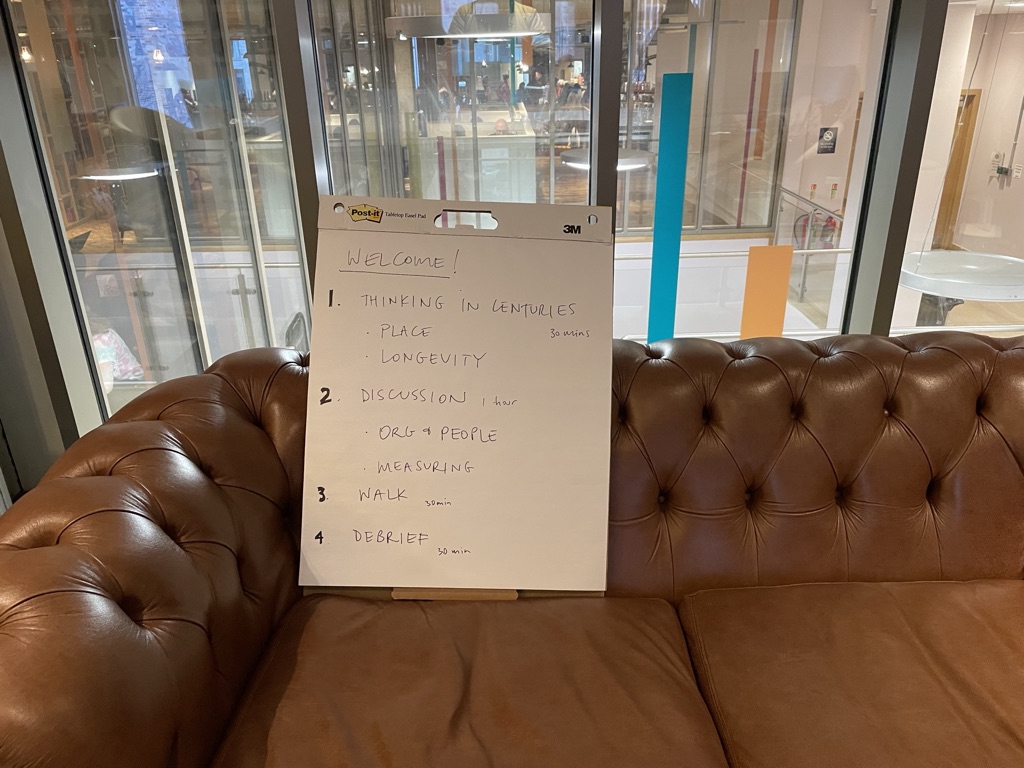

Capturing the reflections, sentiments and future implications raised by Jung and Osaka, these working ‘field notes’ function as a snapshot in time of where we stand as users, creators and curators facing computed image generation. At a time when Artificial Intelligence and Large Language Models are still in their infancy, yet have been recently made widely accessible to internet users, this experiment is by no means an exhaustive analysis of the current state of play. However, by focusing on a single use-case, Edward Steichen’s The Family of Man, Jung and Osaka were able to reflect in greater detail and specificity over a smaller selection of images — and the resultant impact of image generation on this collection.

Observations from this experiment are phrased as a series of conversations, or ‘interfaces’ with the ‘machine’.

Interface 1: ‘That’s not what I meant’

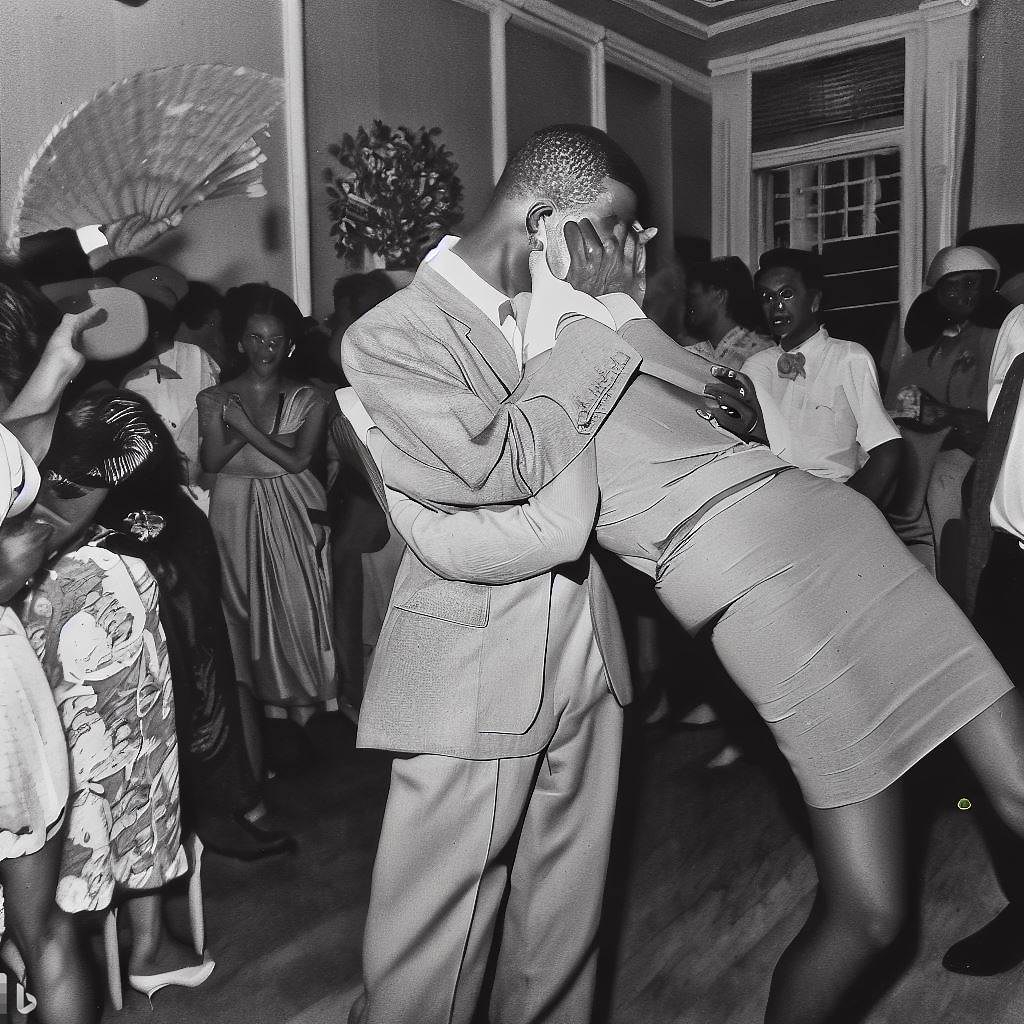

If the aim of image generation is verisimilitude, the first observation to remark upon when feeding captions into image generation tools is there are often significant discrepancies and deviations from the original photographs. AI produces images based on most-likely scenarios, and it became evident from certain visual elements that the generator was ‘filling in’ what the machine ‘expects’. For example, when replicating the photograph of an Austrian family eating a meal, the image generator resorted to stock food and dress types. In order to gain greater accuracy, as Jung explained, “we needed to find key terms that might ‘trick’ the algorithm”. These included supplementing with descriptive prompts of details (e.g. ‘eating from a communal bowl in the centre of the table’), as well as more subjective categories gleaned from the curators interpretations of the images (’working-class’, ‘attractive’, ‘melancholic’). As Osaka remarked, “the human voice in this process is absolutely necessary”. This constitutes a talking with the algorithm, a back-and-forth dialogue to produce true-to-life images, thus further centering the role of the prompt generator or curator.

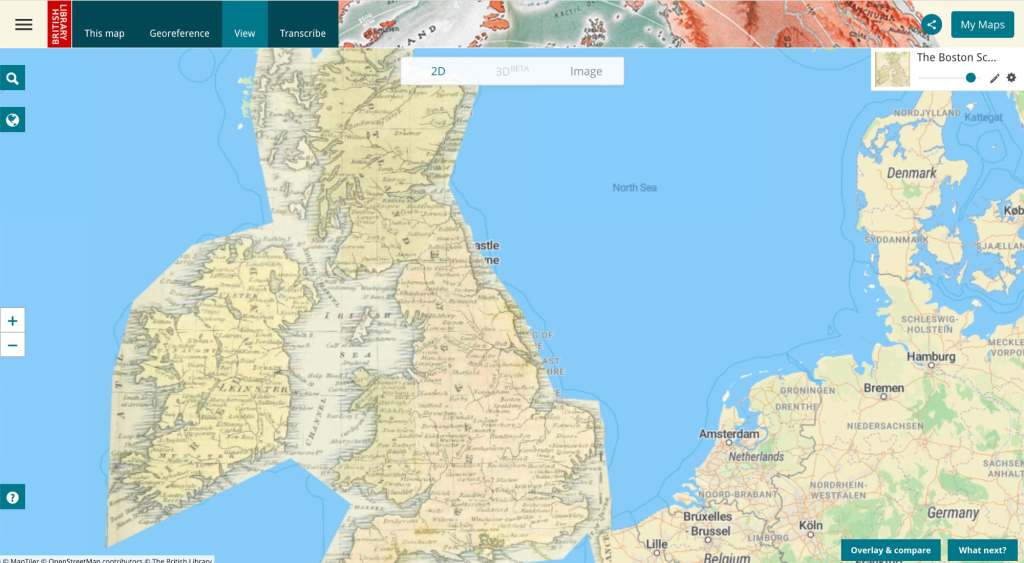

This experiment was not about producing new fantasies, but to test how well the generator could reproduce historical context or reinterpret archival imagery. Adding time-period prompts, such as “1940s-style”, result in approximations based on the narrow window of historical content within the image generator’s training set. “When they don’t have enough data from certain periods AI’s depiction can be skewed”, explains Jung. This risks reflecting or reinforcing biased or incomplete representations of the period at hand. When we consider that more images were produced in the last 20 years than the last 200 years, image generators have a far greater quarry to ‘mine’ from the contemporary period and, as we saw, often struggle with historical detail.

Key take-away:

Generated images of the past are only as good as their training bank of images, which themselves are very far from representative of historical accuracy. Therefore, we ought to develop a set of best practices for projects that seek communion between historic images or archives and generated content.

Interface 2: ‘I’m not trying to sell you anything’

In addition to synthetic image generation, Jung & Osaka also experimented with synthetic caption generation: deriving text from the original images of The Family of Man. The generated captions were far from objective or purely descriptive. As Osaka noted, “it became clear the majority of these tools were developed for content marketing and commercial usage”, with Jung adding, “there was a cheesy, Instagram-esque feel to the captions with the overuse of hashtags and emojis”. Not only was this outdated style instantly transparent and ‘eyeroll-inducing’ for savvy internet users, but in some unfortunate cases, the generator wholly misrepresented the context. In Al Chang’s photo of a grief-stricken America soldier being comforted by his fellow troops in Korea, the image generator produced the following tone-deaf caption:

“Enjoying a peaceful afternoon with my best buddy 🐶💙 #dogsofinstagram #mananddog #bestfriendsforever” (there was no dog in the photograph).

When these “Instagram-esque” captions were fed back into image generation, naturally they produced overly positive, dreamy, aspirational images that lacked the ‘bite’ of the original photographs – thus creating a feedback loop of misrecognition and misunderstood sentiment.

The image and caption generators that Jung & Osaka selected were free services, in order to test what the ‘average user’ would most likely first encounter in synthetic production. This led to another consideration around the commercialism of such tools, as the internet adage goes, “if its free, you’re the product”. Using free AI services often means relinquishing input data, a fact that might be hidden in the fine print. “One of the dilemmas we were internally facing was ‘what is actually happening to these images when we upload them’?” as Jung pondered, “are we actually handing these over to the generators’ future data-sets?”. “It felt a little disrespectful to the creator”, according to Osaka, “in some cases we used specific prompts that emulate the style of particular photographs. It’s a grey area, but perhaps this could even be an infringement on their intellectual property”.

Key take-away:

The majority of synthetic production tools are built with commercial uses in mind. If we presume there are very few ‘neutral’ services available, we must be conscious of data ownership and creator protection.

Interface 3: ‘I’m not really sure how I feel about this’

The experiment resulted in hundreds of synthetic guesses, which induced surprising feelings of guilt among the curators. “In a sense, I felt almost guilty about producing so many images”, reports Jung, with e-waste and resource intensive processing power front of mind. “But we can also think about this another way” Osaka continues, “the originals, being in their analogue form, were captured with such care and consideration. Even their selection for the exhibition was a painstaking, well-documented process”.

We might interpret this as simply a nostalgic longing for finiteness of bygone era, and our disillusionment at today’s easy, instant access. But perhaps there is something unique to synthetic generation here: the more steps the generator takes from the original image, the more degraded the original essence, or meaning, becomes. In this process, not only does the image get further from ‘truth’ in a representational sense, but also in terms of original intention of the creator. If the underlying sense of warmth and cooperation in the original photographs disappears along the generated chain, is there a role for image generation in this context at all? “It often feels like something is missing”, concludes Jung, “at its best, synthetic image generation might be able to replicate moments from the past, but is this all that a photograph is and can be?”

Key take-away: Intention and sentiment are incredibly hard to reproduce synthetically. Human empathy must first be deployed to decipher the ‘purpose’ or background of the image. Naturally, human subjectivity will be input.

Our findings

Our journey into synthetic image generation underscores the indispensable role of human intervention. While the machine can be guided towards accuracy by the so-called ‘prompt generator’, human input is still required to flesh out context where the machine may be lacking in historic data.

At its present capacity, while image generation can approximate visual fidelity, it falters when it attempts to appropriate sentiment and meaning. The uncanny distortions we see in so many of the images of A Generated Family of Man. Monstrous fingers, blurred faces, melting body parts are now so common to artificially generated images they’ve become almost a genre in themselves. These appendages and synthetic ad-libs contravene our possible human identification with the image. This lack of empathic connection, the inability to bridge across the divide, is perhaps what feels so disquieting when we view synthetic images.

As we have seen, when feeding these images into caption generators to ‘read’ the picture, only humans can reliably extract meaning from these images. Trapped within this image-to-text-to-image feedback loop, as creators or viewers we’re ultimately left calling out to the machine: Once More, with Feeling!

We hope projects like this spark the flourishing of similar experiments for users of image generators to the critical and curious about the current state of artificial “intelligence”.

Find out more about A Generated Family of Man in our New Curators program area.