Researcher and digital media theorist, Jill Blackmore Evans, returns to propose four novels principles for Reflective Web Archiving, to engender a more responsible, equitable and usable web archive for the future.

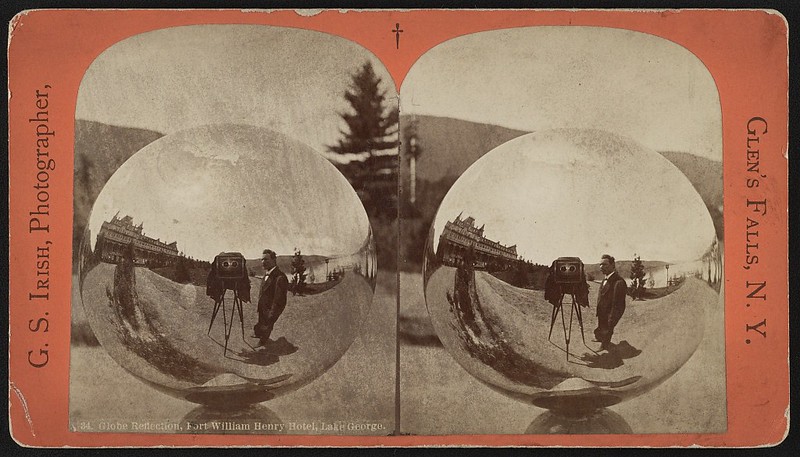

In my first blog post for Flickr.org, The Forgetful Web, I argued for the importance of a consciously reflective approach to web archiving. Through my recent research for my Master’s at Goldsmiths, University of London, I’ve seen how efforts to archive the web by contrast often take a restorative approach, seeking to perfectly recreate past platforms or keep them indefinitely online. Even if they’re well-intentioned, attempts like these often end up calling to mind Jorge Luis Borges’ fantastical short story On Exactitude in Science, in which efforts to create a perfect record of a region result in an impossibly huge and fundamentally useless map that “coincides point for point” with the territory it covers. Applied to web archiving, any faithful reconstruction of a website will inevitably fail to exactly recreate the original.

Trying to reconstruct the past web in this way can be understood as a process of “foreverization,” a term coined by American cultural theorist, Grafton Tanner. To foreverize something means not just attempting “to preserve or restore it but to reanimate it in the present.” Foreverization makes it difficult to move on from what’s past, or to revisit it with a critical perspective.

Instead, foreverizing a web platform means trying to recreate an ideal version of how the platform was at one point in time. This isn’t an effective means of truly archiving the web for future access. The dynamic nature of the web calls instead for an archival approach that acknowledges that not everything online can be saved.

In my previous post, I outlined some of the main issues with how web archiving is often performed, with a focus on social platforms on the web. I noted that archiving the web’s social spaces often takes place as an emergency measure, when a platform is about to be shut down. This means that community members don’t get a chance to reflect on what would be actually meaningful to archive — instead, what gets archived is likely whatever is easiest and fastest to download. And because so much of the web isn’t seen to be worth archiving at all, the job is often left up to volunteers, typically amateur archivists, to make decisions about what to archive and when.

Web archiving today often resembles the following process:

- Attempt to save as much material as possible

- Performed by archivists and/or institutions outside the community

- Focused on the universal over the personal

- Concerned with preservation and restoration rather than recirculation.

Organisations like the Internet Archive do invaluable work in trying to preserve as much of the web as possible through primarily automated methods. Reflective web archiving offers a different approach that’s instead focused on preserving the personal histories of the web. Reflective web archiving acknowledges the impossibility of saving everything on any given web platform, or preserving the platform indefinitely. It embraces the challenge of choosing what to save by focusing on individual stories.

Reflective web archiving means choosing not to save everything, aiming to instead preserve a sample of platform history. And instead of only happening as a last-minute, emergency measure, reflective web archiving is a process that ideally begins while the platform is still operational, in collaboration with the platform’s community.

Reflective nostalgia

My proposal towards reflective archiving is inspired by the work of the cultural theorist, Svetlana Boym, who outlined a theory of nostalgia that is guided by either reflective or restorative impulses. While restorative nostalgia tries to resurrect the past, reflective nostalgia, Boym writes, dwells in loss and “the imperfect process of remembrance.” Nostalgia online frequently takes a restorative rather than reflective form, and web archiving is often focused on restoring the actual pages and platforms of the past web.

The popular understanding of born-digital media suggests that perfectly recreating the online past should be possible, and that all digital media can be safely stored for posterity in “the cloud.” And as Abigail De Kosnik argues in Rogue Archives, the belief that everything online can be archived is reminiscent of one of the earliest fantasies of computing: that computers will be able to perfectly preserve and make accessible all of humanity’s collective history.

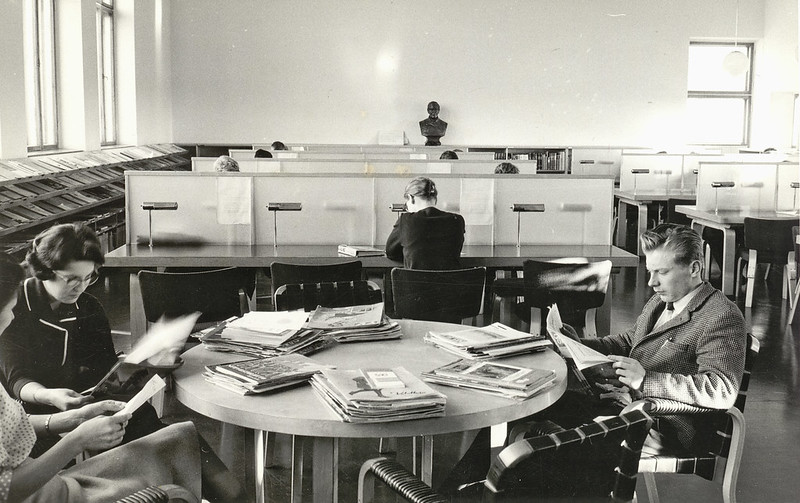

De Kosnik suggests that while the web is often viewed as a “giant memory machine,” automatically building a “total archive” of online activity, the reality is that human volunteers are the ones who actually build this archive. Reflective archiving brings the web back down to a human scale, focusing on preserving personal narratives, not complete histories, for future reflection.

Hereon, I willl outline the four key principles of reflective archiving for the web:

- Reflective archiving accepts that not everything can be saved

- Reflective archiving is guided by community

- Reflective archiving focuses on personal stories

- Reflective archiving encourages recirculation

Principle 1: Accept that not everything can be saved

De Kosnik outlines three major types of web archives: universal, community, and alternative. Web archiving often strives for the universal form, attempting to collect and preserve as much as possible. The Internet Archive, with its original goal of collecting “all publicly accessible World Wide Web pages,” offers a good example of an effort to create a universal archive of the web.

But not everything on the web is included in the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine, especially when it comes to social media platforms with a large number of individual profiles. Trying to locate one’s personal records from old web platforms through the Wayback Machine often leads to disappointment. I was surprised to discover one capture of my deleted Tumblr blog from my teenage years there, but only one page was visible, and none of the links worked.

Efforts to find Flickr profiles from ten years ago are likely to lead to similar dead ends. The Wayback Machine is very helpful in recording what platforms like Tumblr and Flickr looked like in the past, but archiving the enormous volume of personal histories there demands a different strategy — one that accepts the fact that not all such material can be saved.

As De Kosnik suggests, the ideal of the web as a vast memory machine, automatically saving everything uploaded, overlooks the human care needed to actually archive web material. Reflective archiving re-centres this human labour. Instead of striving to preserve as much as possible, reflective archiving is intentionally limited, focusing on saving slices of the web instead of whole platforms.

Reflective archives are not universal archives. They have more in common with De Kosnik’s ideas about community and alternative archives, which focus on preserving material that tends to be overlooked by institutional archives. Born-digital media is often at risk of being overlooked in this way. Institutions may not have the resources to archive social platforms in particular — material types such as comments and photo metadata tend to not fit so easily into the frameworks of typical collections, and the sheer volume of content on social media can make any preservation a daunting task even for established archives.

Reflective archiving seeks to complement more traditional archival practices by creating alternative archives that are highly specific to platform communities and individual users, instead of universal records of entire platforms or periods of time in web history.

Principle two: Be guided by community

Reflective archiving is community-centred. It’s bottom-up rather than top-down, taking place in collaboration with the people whose records are being saved. This means that the community of the platform being archived decides what gets preserved. The platform itself might facilitate the archival work, but the platform users inform decisions around what to save and how to make it accessible in the future.

The community-centred nature of reflective archiving means that:

- Community members can choose what archival content is relevant to their communities, both those on and off the platform

- The content that gets archived is likely to be a more diverse and accurate representation of the activity taking place on the platform and the communities that gather there than it would be if it were selected only by archivists at institutions.

Choosing what to preserve is one of the greatest challenges of archiving the web. Placing community members at the lead of the archival process also means that more people can be involved in selecting material to be archived, helping to not only diversify viewpoints but to distribute the work of archival selection across a larger group of people.

Principle three: Save platform stories, not infrastructure

Archiving web platforms calls for a unique approach because in many ways the content on web platforms is uniquely vulnerable to loss, and also uniquely difficult to archive. There isn’t typically much of an incentive for platforms to create their own archives — after all, if the platform is still live, users can presumably access and download their own data. But in many cases, platforms actively work against user efforts to build their own archives. Individual data downloads may be in formats that are difficult to access or only offer incomplete views of platform activity.

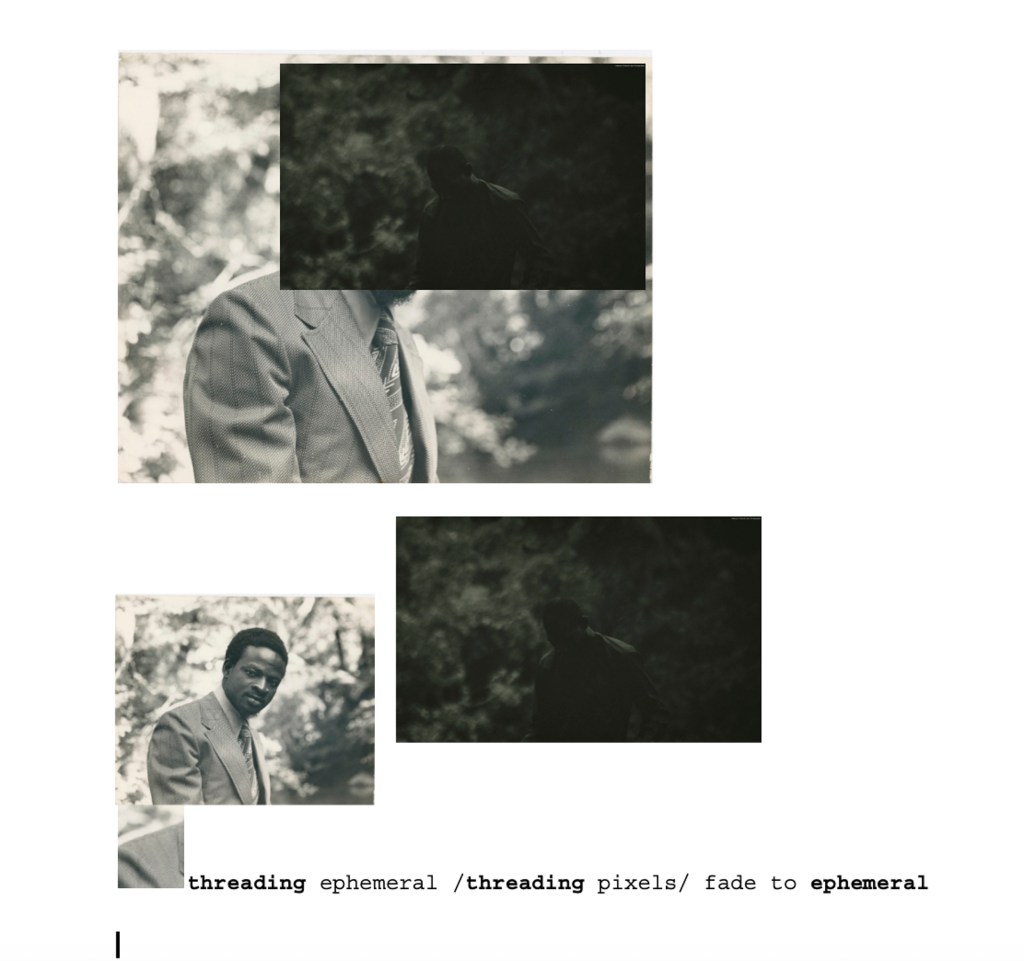

Everything from personal contacts to creative work by users can be abruptly lost when platforms shut down, or even just when technical errors happen: over ten years of Myspace member content was lost in 2019 in a faulty server migration. Reflective archiving acknowledges that even the largest web platforms aren’t infallible: it’s an effort to keep the stories of web platforms accessible even if those platforms disappear, focusing on archiving what users shared online rather than the spaces where that activity took place.

This isn’t to say that archiving platforms themselves isn’t also a worthy task, but it’s one that has to be understood separately from archiving platform contents. Major web platforms are created and owned by private companies, while their contents are created and owned by platform members and communities. Reflective archiving works to save what individuals have created and the context in which it was made, rather than the proprietary structure of the platform itself.

Principle four: Encourage recirculation.

Web archiving, much like the web itself, is still relatively new. De Kosnik points out that much of the digital artifacts of the past few online decades may disappear entirely in the next few hundred years — though “much of the current digital repertoire” may still be used. “The repertoire of conversing via telephone has persisted into the digital age,” she notes, although the vast majority of telephone conversations were never archived.

De Kosnik argues for the importance of “repertoires for digital archiving,” suggesting that the archival practices being developed today may continue to be relevant far into the future, even if the archives themselves are no longer accessible.

Reflective web archiving can be considered a specific archival repertoire informed by the principles outlined here, including this final one: recirculation. Arguably any effort to archive the web demands a kind of recirculation; when the web is archived, it must be “reborn,” as Niels Brügger describes in The Archived Web. “The online web must be collected, preserved, and made available as the archived web,” and through this process, it is reconstructed and changed.

The web can never be really perfectly preserved. Reflective web archiving focuses more on the continued availability of records of the past web rather than their exact restoration. This means ensuring that what gets archived isn’t simply stored on a hard drive somewhere, but is also made available for future use.

Conclusion

Not only are records of the web’s earliest years limited, much of Web 2.0 is also quickly disappearing. Archiving the web of today is a much more difficult task due to its larger size — but this is also why it’s so important. Embracing a reflective approach to web archiving can help make the work of web archiving more accessible by putting the focus on the personal rather than the universal.

A web archive that follows the principles of reflective archiving has the ability to preserve slivers of a platform that, through their specificity, offer a genuine look back at the platform’s history. And the community members who inform the work of reflective web archiving have the ability to guide how their own histories are recorded for the future, and ensure that they have the chance to look back on their online past, even if the platforms of the past are long gone.

“Nostalgia is not always about the past; it can be retrospective but also prospective,” Boym wrote in The Future of Nostalgia. Reflective nostalgia doesn’t have to only inspire mourning for what’s gone: it can also “present an ethical and creative challenge,” she suggested. Reflective archiving takes up the challenge of how to preserve records of collective online memory for the future, embracing the creative potential of archiving’s limitations.

Bibliography

Boym, Svetlana. The Future of Nostalgia. New York: Basic Books, 2001.

Brügger, Niels. The Archived Web: Doing History in the Digital Age. Cambridge, Massachusetts:

The MIT Press, 2018.

De Kosnik, Abigail. Rogue Archives: Digital Cultural Memory and Media Fandom. Cambridge

Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2016.

Tanner, Grafton. Foreverism. Medford: Polity Press, 2023.