Earlier this month, I attended the Rijksmuseum’s compelling symposium Future Memories: How Photography Shapes Our Understanding of the World, co-led by the World Press Photo Forum. This day-long exploration of photojournalism and documentary photography felt particularly relevant to our work at the Flickr Foundation, especially as we grapple with how emerging technologies are reshaping our shared visual language.

Whose Stories Get Told? Challenging the Dominant Visual Lens

The first theme that struck me speaks to the ongoing photographic issue of representation: whose perspectives dominate our visual culture, and by extension, whose inevitably gets sidelined?

Dutch art historian, Wieteke van Zeil, delivered a sharp critique of viral “accidental Renaissance” photos that circulate online every few years. While undeniably entertaining, she argued that our reliance on Western visual tropes — such as a pietà, a deposition from the cross, a genre scene — reveals how our eyes are “trained,” (to use John Berger’s terminology for the social, historical and political context that sits behind our eyes) to find comfort and comprehension in familiar compositional languages. This creates a kind of visual playbook that aspiring photojournalists and photo publishers unconsciously follow to expand their reach, perpetuating a narrow way of seeing the world.

The symposium didn’t stop at pure critique, it offered compelling alternatives. Photo editor and curator, Tanvi Mishra, proposed several photographic collections operating outside of these dominant modes. These images, often deriving from locales where historically the camera has been used a tool of constructing colonial control, play with the dynamic of visibility and refusal. They prompt the question of not simply “who gets to be seen?” but also “under what conditions?” We find this critique particularly pertinent to the Flickr archive as we hold a massively diverse body of images, arguably one of the most diverse online given its crowdsourced nature. As algorithmic cultures on platforms increasingly prioritise certain visual elements and tropes (e.g. posting a face in a thumbnail or first frame, hands or pointing gestures, certain aspect ratios also known as algorithmic folklore), we need to ask, how can we support content that isn’t continually chasing the (Western-prescribed) algorithm to spotlight alternative forms of visual communication.

Mishra presented Rayyashi Goody’s photographic collection, Eat With Great Delight (2018), as a visual explication of the reclamation of narrative control. Goody, herself raised in a half-Dalit, half-English family, uses photographic and culinary representations to “call attention to Dalit communities’ everyday struggle and resistance under the caste system”. With images from her family archive taken between 1984 and 2004 on point-and-shoot film cameras, Goody showcases the contradictory emotions of “hunger and shame” alongside “satiation and celebration”. For instance drawing particular attention to the practice of ‘joothan’, the act of gathering leftovers from upper caste wedding feasts, Goody rejects the singular “authoritative forms of visuality” rooted in both colonial and social systems of oppression.

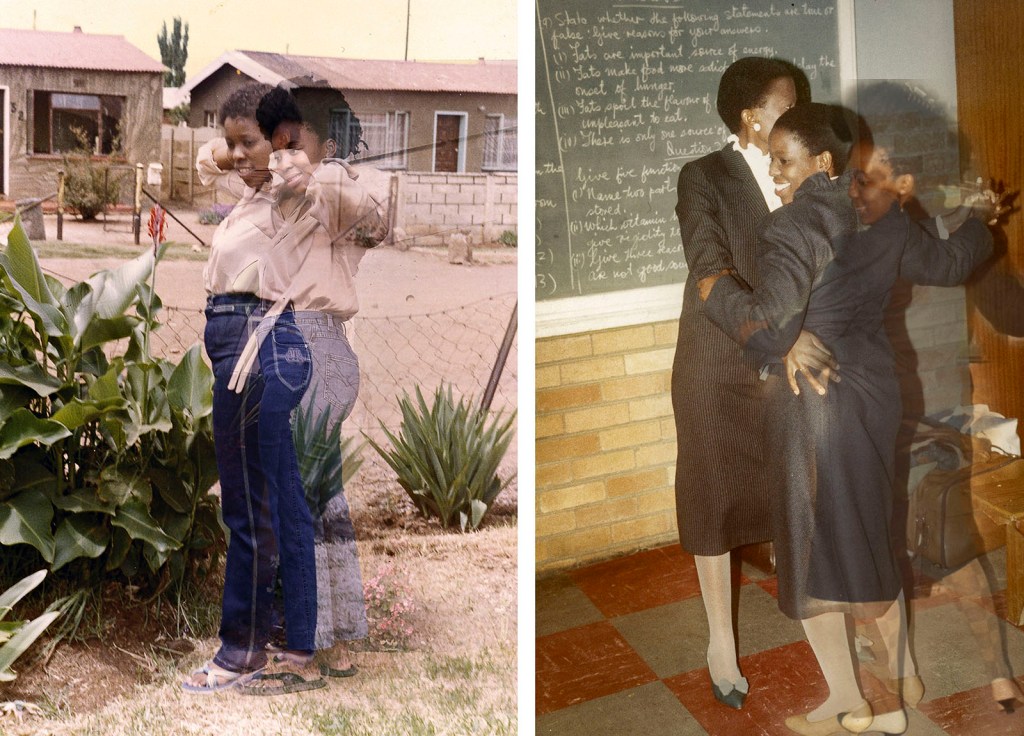

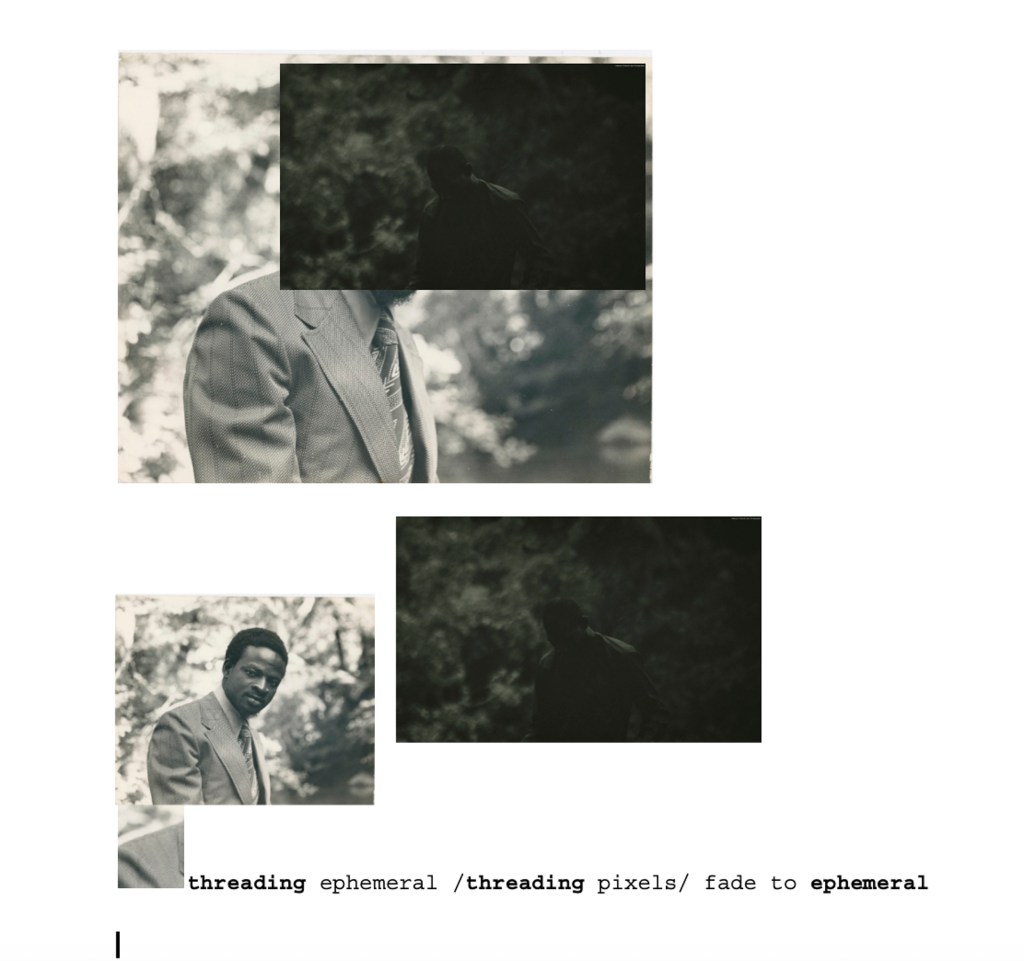

In another striking example of visibility under self-determined conditions, keynote speaker Lebohang Kganye shared her photo series, Ke Lefa Laka: Her-Story (2013). Following the death of her mother, Kganye restaged scenes from found family photographs, layering herself into the images while wearing her mother’s clothes, sparking an extended dialogue with the past. Kganye shows how photography provides not just an opportunity to reconstruct the world but as an active tool to work through grief and memory. Speaking to the criticality of family photos in the wider political context, as Kganye noted, during apartheid, the Black South African photo album was one of the few spaces where Black families could represent themselves and tell their own stories. A story that Kganye herself continues today.

For the Flickr Foundation, this speaks to the importance of preserving generational histories that live nestled within the Flickr archive. It prompts us to ask, how we might ensure these photos are well for preserved not just for familial safekeeping but also creative and curative re-interpretation?

From ‘Writing with Light’ to the ‘Black Box’: Photography’s Technological Dilemma

The second theme that emerged during Future Memories considers emerging technology’s reshaping of the photographic medium itself. Keynote speaker, Joanna Zylinska, reflecting on the creeping volume of synthetic images posed the question, “what happens when photography gets removed from the human eye?” She argues, the distinction between image capture and image creation has, in recent years, blurred beyond recognition. From dual-pixel autofocus to depth sensors, machines mediate our vision before we even look through the viewfinder. Increasingly machines share images with one another, without the need for a human set of eyes.

An example of this ‘machine vision’ is found in the work of Trevor Paglen, whose interrogation and bringing forth of the technological ‘unconscious’ nestled in digital photography. On his 2020 series, Clouds, an ongoing interrogation of how computer vision ‘sees’ the world, Paglen writes, “the cloud formations shown in these works are overlaid with strokes and lines depicting what various computer vision algorithms are “seeing” in the images.” Paglen’s approach brings forth and makes visible (and thus subject to critique) the hidden language of what Zylinska coins sensography, the supplanting of the photographic medium with the primacy of sensors.

Rather than rejecting enroaching synthetic mediation entirely — an impossible task — Zylinska suggests we ought to “identify moments when the programmability of its system fails. In doing so we might gain something.” This means thinking through machines rather than attempting to think outside them entirely, an idea she expands upon in her 2023 book, The Perception Machines: Our Photographic Future between the Eye and AI. The “after-photographic moment” we find ourselves in presents both opportunities and warnings, particularly when we consider questions of provenance and truth in photojournalism, or any photographic medium with claims to truth.

An outstanding technological question hung heavy over the symposium, explictly called out by Rijksmuseum photo curator, Mattie Boom, in her closing remarks. How should we be thinking about the platforms where the majority of this photographic work is performed and hosted? Today’s photographic consumption and increasingly, production is mediated by social media platforms with rapidly shifting policies, politics and incentive structures. These platforms don’t just distribute images; they actively shape how images are created, who sees them, and what kinds of visual stories get shared and saved. As the Flickr Foundation, we would like to propose a deeper examination of this topic in the months to come.