Researcher and digital media theorist, Jill Blackmore Evans, discusses the challenges of web archiving and investigates the relationship between online nostalgia, archiving, and indefinite preservation; arguing for the importance of an archival approach informed by reflective nostalgia.

Just as historians rely on physical media like newspapers and photographs to interpret the pre-digital past, it’s obvious that we’ll need future access to records of the web to be able to study the present. The more the web grows, the more important archiving it becomes, but this task also becomes increasingly difficult. With so much of our lives taking place online, how do we decide what to save?

Archivists and librarians have been discussing the prospect of a “digital dark age” since the 1990s, and the myth of the web’s endurance plays a large part in contributing to this risk. “Digital storage is easy; digital preservation is not,” Stewart Brand wrote in 1999. Yet the belief persists that when something’s been shared online, it will be available forever, and there’s no need to worry about archiving it.

Since 1996, the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine has tried to make this a reality by saving as much of the web as possible. But even though it’s saved over 928 billion web pages to date, the Wayback Machine can’t archive everything online, especially when it comes to social media platforms with millions of dynamic user profiles.

One of the biggest challenges of web archiving today lies in the fact that so much activity on the internet now takes place on social media. When these platforms get deleted, not only do users often lose access to their personal data, but future historians lose access to records of our time. Live platforms can be difficult to archive due to the volume of content and activity over time, but doing so is crucial for our understanding of web history.

In my recent research for my Master’s at Goldsmiths, University of London, I investigated the challenges of web archiving and the rise of nostalgia for the online past. Nostalgia for the web’s early years has grown online as that time period recedes further into the past — not only in the usual sense of time passing, but also because records of those years are increasingly inaccessible. This nostalgia has contributed to the trend of efforts to “foreverize” the web by reviving the platforms and aesthetics of Web 1.0.

In this post, I’ll draw on this work to discuss online nostalgia and the challenges of web archiving. Web archiving today often takes a restorative approach, as seen in nostalgic efforts to rebuild old platforms or even preserve them indefinitely. I’ll discuss the importance of a more reflective nostalgia in deciding how to archive online platforms. Instead of trying to preserve everything we can from the past web, a reflective approach to web archiving embraces the fact that not everything online can be saved or restored.

The forgetful web

Just because the web itself appears accessible anytime that doesn’t mean specific web content always will be. Media theorist Wendy Chun describes this state of affairs as an “enduring ephemeral,” writing that “memory, with its constant degeneration, does not equal storage.” In Rogue Archives, Abigail De Kosnik highlights the tension between the ideal of the internet as a “giant memory machine”, in short an archive, capable of storing users’ web histories and the reality: that the web can only effectively function as this archive thanks to the work of human volunteers.

In fact, “the web tends to forget all by itself,” media studies scholar Niels Brügger writes in The Archived Web. The only way old websites and online media can stay accessible is if someone has previously “taken the initiative to collect and preserve the web and to make it available for research purposes.” If no one does this, then records of online history may eventually disappear. Just like physical media, online media needs a certain amount of maintenance and care to survive.

Online nostalgia

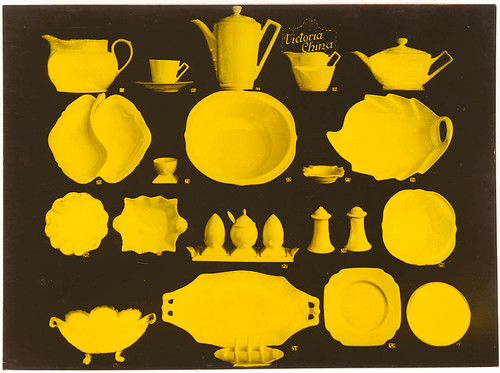

As more and more records of the web’s early years fade away, a growing sense of nostalgia for the past web has emerged online. The amateur aesthetics of Web 1.0 have come to be seen as charming retro-kitsch, and people of all ages talk about longing to return to the simpler days of personal websites. The early web hosting platform Geocities, founded in 1994, has come to represent a particular nostalgic ideal of the old web, as seen for example in the 2015 digital collage Cameron’s World, a “tribute to the lost days of unrefined self-expression on the Internet.”

The musical genre vaporwave, which emerged in the 2010s, took inspiration from the aesthetic of the early web; in the 2020s, nostalgia for Web 1.0 continues to influence online visual culture and music through the aesthetics of “webcore” and “internetcore”. Photos of old desktop computing setups go viral on social media, inspiring nostalgic comments about the pre-smartphone era.

In her influential book The Future of Nostalgia, the cultural theorist Svetlana Boym argued that “obsession with the past” often occurs in “inverse proportion to its actual preservation.” Without reliable records of the web’s early years, it’s easy to idealise the online past and wish we could go back to that supposed golden age — a simpler time before targeted advertising and AI spam.

Boym outlined a theory of nostalgia that offers a useful perspective for thinking through the longing for the past web. She proposed “restorative” and “reflective” as the two main types of nostalgia, writing that

“restorative nostalgia protects the absolute truth, while reflective nostalgia calls it into doubt.”

Restorative nostalgia attempts to faithfully reconstruct the lost home (or homeland) of the past. It lacks the self-reflexivity of reflective nostalgia.

Restorative nostalgia can be seen in efforts to rebuild damaged monuments of the past. Boym describes the controversial restoration of the Sistine Chapel frescoes in the 1980s, an effort to remove all “material traces of the past” from Michelangelo’s work, as an example of restorative nostalgia.

In contrast, reflective nostalgia embraces the patina and imperfection of ruins. While restorative nostalgia sees the past as something that can be perfectly remade, reflective nostalgia acknowledges its “inconclusive and fragmentary” narrative, making room for ambivalence and contradiction.

Wanting to rebuild Geocities in the present is an example of restorative nostalgia, while looking through the Geocities archive can offer a chance to reflect. When the platform was shut down in 2009 by Yahoo, it was partially archived due to the emergency preservation work of the Archive Team, a collective of volunteer archivists who acted to download as much of Geocities as possible before it went offline. Because of this voluntary labour by people who were passionate about saving web history, an archive of about one terabyte of Geocities data is now publicly available for free download today at the Archive Team’s website.

The accessibility of this archive has made possible efforts to restore Geocities, such as The Deleted City, a 2017 “interactive visualisation” of the Archive Team download, and The Geocities Gallery, a 2019 attempt to recreate the platform by hosting a browsable version within the live web. Although projects like these may seek to recreate Geocities as much as possible, the fact that only part of the platform was saved limits any reconstruction efforts. When it comes to the past web, restorative and reflective nostalgia often coincide.

Challenges of web archiving

The story of Geocities highlights some of the key problems with web archiving, which hold important lessons for archiving other large-scale social platforms like Flickr:

- Web archiving often happens in a reactive state, as an emergency measure when a platform is about to be shut down. This means that what gets archived may just be whatever material is easiest and fastest to download, rather than what offers a representative view of the platform.

- Archiving a platform right before it goes offline likely means only saving what is currently available, as older content may already be inaccessible.

- It’s often left up to volunteers, typically platform users and amateur archivists, to decide what to save.

De Kosnik highlights the importance of “rogue archives” online, noting that digital archiving has been primarily embraced by “‘rogue’ memory workers” such as “amateurs, fans, hackers, pirates, and volunteers.” She discusses the fan fiction database, Archive of Our Own, as a case study of an volunteer-run archive created by fans, for fans. The Archive Team, which bills itself as “a loose collective of rogue archivists,” offers another example.

Unauthorized and alternative archives can be a powerful tool for preserving histories that may otherwise be overlooked by institutions, but we shouldn’t rely too much on unpaid enthusiasts to preserve web history. Web archives can be costly to maintain, and it’s crucial that institutions and governments also support this work.

Foreverizing the web

Web archiving isn’t necessarily about recreating the past web, but efforts to do so have become popular online in recent years, as outdated web platforms get remade through the process of “foreverization.” This term comes from the work of Grafton Tanner. In his book Foreverism, Tanner discusses the recent trend of frequent movie remakes, sequels, and prequels as one example of foreverization. As he describes it, “to foreverize something is not merely to preserve or restore it but to reanimate it in the present and ensure its future survival, forever.”

Similar to Boym’s restorative nostalgia, foreverization is motivated by an inability to let go of the past. While restorative nostalgia is an effort to rebuild what has already been lost, foreverization is a process that aims to stop the past from disappearing. Tanner describes it therefore as a kind of anti-nostalgia. After all, you can’t miss what isn’t actually gone. In his view, foreverizing works to “extinguish nostalgia while also profiting from it.” Foreverizing profits from the desire to return to the familiar while making critical engagement with the past more difficult.

Just as popular movies from the recent past keep getting rebooted, old web platforms are also being foreverized. In the last few years, outdated websites such as Neopets and Habbo Hotel have been rebooted in attempts to recreate the web’s “good old days”. These two virtual worlds were both hugely popular with millennial kids in the 2000s and have now returned in attempts to capitalise on the nostalgia of their former users.

Here we can see the distinction between restorative nostalgia and foreverization as approaches to recreating the past web. Trying to bring Geocities “back to life” in the contemporary web is a form of restorative nostalgia because it’s an effort to remake the past, not as “a duration but a perfect snapshot,” as Boym describes the restorative impulse. But unlike Geocities, Neopets and Habbo Hotel never actually went offline. Launched in 1999 and 2000 respectively, both websites have remained active for over twenty years, but their popularity dwindled as the broader web changed and their users got older.

Neopets announced a revitalized site in 2023 with the stated aim of bringing back the platform’s “glory days,” while Habbo Hotel’s 2024 launch of “Habbo Hotel: Origins” sought to recreate the platform exactly “as it existed in 2005.” Reboots like these appeal to the narrative of web foreverization which asserts that life was more authentic on the early web, and that creating a better future online is possible if we can only keep that past alive.

Tanner describes foreverizing as making “small upgrades constantly within a closed system.” Foreverizing the early web uncritically resurrects the techno-utopian philosophy of that time, keeping us stuck in that same system and preventing critical reflection on how the old web really was.

Recording the landmarks of everyday life

Attempts to restore the past web can distract from the need to archive records of the present web. But so much of what’s online, especially on social media platforms, is often seen as not worth saving. After all, these are just the traces of everyday life. Choose a photo from a platform like Flickr at random and chances are that it isn’t all that meaningful to anyone besides the person who shared it and their community. Of course, out of all those photos, there will also be many that do have broader significance as records of historical events, for example.

At scale, even the seemingly random personal images and comments shared on platforms like Flickr are also important records of our social history and visual culture. They are part of what makes up our collective memory. What gets shared on social media are “the common landmarks of everyday life” that, as Boym puts it, “constitute shared social frameworks of individual recollections.”

A restorative approach to web archiving puts the focus on recreating or preserving the platforms of the old web, “reconstructing the emblems and rituals” of a past home, as Boym writes. In contrast, archiving that’s inspired by reflective nostalgia dwells in the details, seeking to preserve not the past functionalities or structures of the web but the everyday interactions that took place there.

One Terabyte of Kilobyte Age exemplifies a reflective nostalgia approach to engaging with the online past. For more than ten years, the artists Olia Lialina and Dragan Espenschied have recirculated the web pages in the Geocities archive, both through writing and via a Tumblr blog which has shared hundreds of thousands of screenshots of the archive. Writing about the project in Documentation as Art, Annet Dekker and Katrina Sluis suggest that it “shows how preservation is not necessarily always about maintaining and fixing the original.” Instead of trying to recreate Geocities, One Terabyte thoughtfully interrogates and recirculates the histories the archive contains.

With a platform as large as Geocities, a reflective approach is needed to make sense of the collective history found there. The One Terabyte blog reflects on selected content from the archive, thereby asking “what preservation could mean in the context of amateur digital preservation,” as Dekker and Sluis argue.

A reflective archival approach that focuses on a representative selection of content can help preserve the collective memories of large web platforms. The Flickr Foundation’s Data Lifeboat program is an example of one such effort, offering a toolkit anyone can use to archive their own selection of Flickr. Many social media platforms allow users to download archives of their own data, but the Data Lifeboat also allows for the archiving of other people’s content, facilitating the creation of archives that document a community, place, or time.

While Data Lifeboats can also work to archive platform-specific data such as photo tags and user comments, the program is not an effort to preserve Flickr as a web platform. Web archiving entails preserving records of information such as how platforms looked, the way in which they operated, and of course their contents.

Web archiving doesn’t seek to maintain platform functionality, which might require restoration work or even a full recreation of the platform if it has gone offline. The goal of web archiving isn’t to bring the past back to life, but to ensure that records of that past remain available.

Conclusion

By uncritically seeking to rebuild what’s been lost, foreverization risks recreating the conditions that led old web platforms to be shut down or abandoned in the first place. There’s a lot wrong with the web today, from inescapable ads to corporate monopolies, but simply trying to return to how things used to be isn’t a realistic solution.

Web archives are essential in enabling study of the web’s history and helping us chart a path for an improved web in the future. We can’t indefinitely preserve the web as it currently is, and we can’t perfectly recreate its past either. What archiving can do is help keep accessible those collective frameworks of memory that emerge online, making possible the conditions for future study and reflection.

Bibliography

Boym, Svetlana. The Future of Nostalgia. New York: Basic Books, 2001.

Brügger, Niels. The Archived Web: Doing History in the Digital Age. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2018.

Chun, Wendy Hui Kyong. “The Enduring Ephemeral, or the Future Is a Memory.” Critical Inquiry 35, no. 1 (September 2008): 148–71. https://doi.org/10.1086/595632.

Dekker, Annet, Katrina Sluis, and Olia Lialina. “One Terabyte of Documentation: The Circulation of GeoCities.” In Documentation as Art: Expanded Digital Practices, edited by Annet Dekker and Gabriella Giannachi, 120–30. New York, NY, USA: Routledge, 2022.

De Kosnik, Abigail. Rogue Archives: Digital Cultural Memory and Media Fandom. Cambridge Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2016.

Tanner, Grafton. Foreverism. Medford: Polity Press, 2023.