In seeking forebears for our Digital Daybook, we turned to the archives to ask: Where do daybooks most frequently appear, and for what purposes were they used?

At their core, daybooks have historically served as practical tools for record-keeping, most often in business and administrative contexts. Before formalised accounting systems, they provided a means to track transactions, exchanges, and daily operations. Daybooks not only reveal how societies organised trade, labour, and governance but also how they configured systems of trust, communication and memory.

Grain and Goddesses: Mesopotamian Cuneiform

Perhaps one of the earliest iterations of the daybook can be found in Mesopotamian cuneiform tablets, some dating as far back as 3100 BCE. These clay records, impressed with pictographic signs, documented economic transactions, resource distributions and contracts. In Uruk, modern-day Iraq, these tablets reveal a world where grain, pottery, livestock, and textiles flowed through complex trade networks. Crucially, they also capture a society where trust was fast becoming a critical currency—particularly in enabling trade between people beyond immediate social or familial circles. The web of transactions reflects the burgeoning complexity of their society, where record-keeping was not just administrative but an essential tool for managing expanding economies.

These tablets reflect not only trade and social organisation but also cosmological rituals. One remarkable example is Tablet W 05233,b, which records the distribution of different types of grain products to celebrate the festival of the evening star, dedicated to the goddess Inanna—later known as the Assyrian Ishtar or Greek Aphrodite. Here, the act of recording wasn’t just about economic order; it was also about ritual, encoding celestial cycles into daily life (something we’ll return to in a later example).

The level of detail embedded in these small clay tablets is remarkable. Besides flat pictorial representations of traded goods and their quantities, cuneiform records introduced a third dimension of depth. Contracts were often signed using bullae, hollow clay balls, with designs inscribed to mark ownership, identify witnesses or partners in commerce. Here we see the very terms of the contract were impressed into the material. In some cases the fingerprints of the person who made the impression remain visible on the clay.

Often cited as one of the earliest writing systems, cuneiform represents a shift from recording merely “how many” to capturing the contextual detail of “where, when, and how.” For our own Digital Daybook, this invites us to consider how we can convey meaning beyond transactional value—and perhaps, like the bullae, inspire ways to embed materiality into our own system.

Furs and Fusils: The Daybooks of the Hudson’s Bay Company

Millennia later, in a vastly different context, daybooks reappear in the ledgers of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), providing a granular account of the daily workings of a colonial enterprise.

Founded in 1670, the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) fast became the dominant force in the North American fur trade, operating as a commercial empire backed by English royal charter. While the company controlled vast tracts of land and waterways, its success depended on a delicate balance: Indigenous trappers and middlemen were essential suppliers of furs. The HBC trading posts functioned as sites of negotiation, exchange, and economic entanglement, the details of which can be traced throughout its daybooks.

HBC daybooks meticulously document what was traded and for how much, but beneath their factual, transactional surface, a deeper story of economic dependency emerges as Stephen R. Brown details in The Company: The Rise and Fall of the Hudson’s Bay Empire. Indigenous trappers brought furs to trading posts in exchange for goods—ammunition, wool blankets, sugar and alcohol—that had become increasingly necessary for survival as colonial expansion disrupted access to their traditional resources. At the same time, European markets dictated the value of Indigenous goods, with prices and demand calibrated through these ledgers. While the records present trade as a system of mutual exchange, the daybooks reveal how European economic logic was imposed onto Indigenous ways of life, reshaping labour, production and survival itself.

What goes unrecorded in the daybooks is just as telling as what is logged. Daybooks meticulously note the number of furs exchanged but omit the labour required to trap them. The names of indigenous trappers rarely appear, nor do the details of their communities. Women, in particular, remain largely invisible, as historian Sylvia Van Kirk explains in Many Tender Ties: Women in Fur Trade Society, 1670-1870. Canadian traders were explicitly told that “an Indian mate could be an effective agent in adding to the trader’s knowledge of Indian life”. This call for linguistic and cultural mediation conceals within it the emerging gendered economy and the instrumentalisation of the Indigenous female body.

In this way, daybooks constitute a “figure under the carpet,” a term coined by historian James Atlas to describe the unseen but essential forces shaping history—if we’re willing to read between their ledger lines. Daybooks don’t just document transactions; they expose hidden histories of organisations and their interweavings with social fabric writ large.

Which should prompt us to ask: How might our Digital Daybook reveal the assumptions, conditions, and politics that underpin the Flickr Foundation and its daily workings?

Rishu and Rosary: Divination and Alchemy in Daybooks

If we expand the concept of the daybook beyond its fiscal and administrative functions, and consider the broader world of record-keeping, we might chance an encounter with daybooks’ more mystical cousins.

In the 2nd century BCE, daybooks—known as rishu (日書)—were used in Han Dynasty China to plot auspicious and inauspicious days. This hemerological use case shows how daybooks were used to record and plan the cosmological fortunes of the year. By plotting one’s activities—agriculture, travel, business, marriage—against the rishu, individuals could align their actions with cosmic rhythms. As Richard Smith writes in Books of Fate and Popular Culture in Early China, these daybooks appear “not simply as information transferred onto written media, but as a constituent of daily life realized anew in each manuscript.” Thus, rishu daybooks were not only descriptive but prescriptive—they structured time rather than simply logging it.

Crucially the rishu suggest a shift from the divination model to recorded experience. Earlier traditions of oracle bones, tasseography, and cleromancy relied on chance and external omens, whereas these daybooks tracked patterns, tested outcomes, and built knowledge through lived observation. They capture an emerging sense of human agency over fate—a written interface between knowledge, ritual, and daily life.

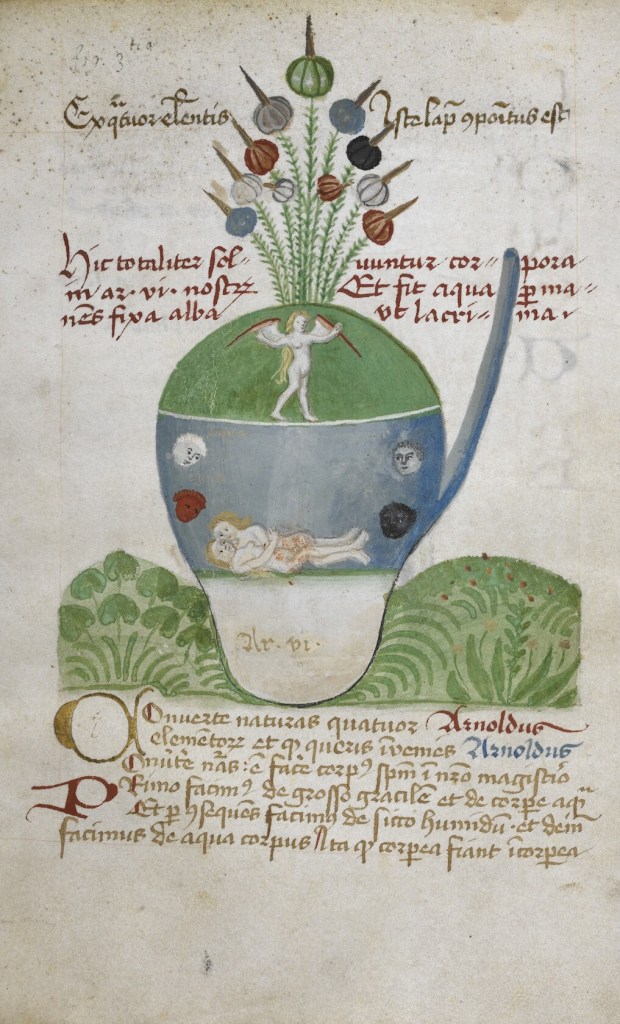

Much like the rishu daybooks, alchemical records were not just passive repositories of data but tools for dynamic experimentation. Often dismissed today for their fantastical contents and purposely obfuscating esotericism, they were critical stepping stones in the history of Western scientific inquiry. Alchemical records—such as Paracelsus’ Opus Paramirum (1531) or anon.’s Rosarium Philosophorum (1550)—captured trial and error, cycles of progress and failure, and patterns that could only emerge over time. Part laboratory record, part philosophical meditation, part mystical vision—these texts foreground the individual’s observations, a contrast to modern scientific inquiry, which often seeks to depersonalise the process of knowledge and meaning-making. Alchemical logs offer the daybook as a potential site of iterative knowledge-building, where reflection is as critical as logging day-to-day activities.

Whilst we don’t (yet!) propose a spiritual undertaking at the Flickr Foundation, these examples encourage us to consider how might we construct our Digital Daybook to reflect on the unknown, embrace the speculative, and remain open to the unpredictable.